A pathological condition that is accompanied by a decrease in the size, volume and weight of an entire organ or its individual sections with a gradual cessation of functioning is called atrophy.

This disease can affect various organs and tissues, in particular muscles, brain, limbs, retina, and skin. Atrophy can develop as a result of disease and also as part of the natural aging process. In this regard, senile and pathological atrophy are distinguished.

Symptoms

Depending on the nature of the lesion, location, severity and prevalence, various symptoms of the disease appear. Thus, general muscular atrophy is characterized by thinness, loss of muscle mass, and exhaustion. The progression of this pathology leads to atrophy of brain cells and internal organs.

With retinal atrophy, there is a loss of clarity of vision, as well as the ability to distinguish colors. As vision deteriorates, the patient develops optical illusions and develops complete blindness. Skin atrophy is characterized by loss of elasticity, thinning and dryness.

Vaginal atrophy: etiological aspects and modern approaches to therapy

Postmenopause is characterized by an estrogen deficiency state in women, caused by age-related decline and then cessation of ovarian function [1]. As is known, any epithelial tissue reacts to changes in the hormonal environment surrounding them in a similar way, but none of them can compare with the epithelium of the vaginal vault and cervix in the speed and clarity of the reaction to hormones, primarily to sex steroids [2]. Thus, the urogenital tract is particularly sensitive to decreased estrogen levels and approximately half of all postmenopausal women experience symptoms associated with urogenital atrophy (UGA), affecting sexual function and quality of life [3]. The clinical picture of urogenital disorders in the menopause includes symptoms associated with vaginal atrophy (vaginal atrophy (VA)) and urination disorders (cystourethral atrophy). Unlike vasomotor symptoms, which usually resolve over time, symptoms of vaginal atrophy typically begin in premenopause and progress postmenopause, leading to functional and anatomical changes [4]. 15% of premenopausal women and 40–57% of postmenopausal women experience symptoms of VA [5], such as vaginal dryness 27–55%, burning and itching 18%, dyspareunia 33–41%, as well as increased susceptibility to infectious diseases of the organs pelvis 6–8% [4], which significantly worsens health and negatively affects the general and sexual quality of life [6]. 41% of women aged 50–79 years have at least one of the symptoms of VA [10].

The walls of the vagina consist of three layers: the inner layer, which is lined with stratified squamous epithelium; middle muscular and outer connective tissue layers (or fibrous layer). Atrophic processes involving the connective tissue and muscle structures of the vagina, as well as the muscles of the pelvic floor, urethra, and bladder, are especially pronounced in the vaginal mucosa. It is known that in women, the vaginal mucosa consists of four main layers of epithelial cells: the basal layer; parabasal layer (or mitotically active); intermediate glycogen-containing layer; superficial (flaking) [11]. Estrogen receptors are located mainly in the basal and parabasal layers of the vagina and are practically absent in the intermediate and superficial layers [10]. Estrogen deficiency blocks the mitotic activity of the basal and parabasal layers of the epithelium of the vaginal wall, and, consequently, the proliferation of the vaginal epithelium [12]. The consequence of the cessation of proliferative processes in the vaginal epithelium is the disappearance of glycogen, a nutrient medium for lactobacilli, thus its main component, lactobacilli, is completely eliminated from the vaginal biotope [3, 12].

It is known that peroxide-producing lactobacilli, which predominate in vaginal microbiocinosis in women of reproductive age, play a key role in preventing the occurrence of diseases of the urogenital tract [10, 11]. Due to the breakdown of glycogen, which is formed in the vaginal epithelium, provided there is a sufficient amount of estrogens, lactic acid is formed, providing an acidic vaginal environment (within pH fluctuations from 3.8 to 4.4). Such a protective mechanism leads to suppression of the growth of pathogenic and opportunistic bacteria. During the postmenopausal period, the vaginal mucosa loses these protective properties, becomes thinner, and is easily injured, followed by infection not only by pathogenic, but also by opportunistic microorganisms.

Estrogens are the main regulators of physiological processes in the vagina. Estrogen receptors α are present in the vagina in premenopausal and postmenopausal women, while estrogen receptors β are completely absent or have low expression in the vaginal wall of postmenopausal women. The highest density of estrogen receptors is observed in the vagina and decreases in the direction from the internal genital organs to the skin. The density of androgen receptors, on the contrary, is low in the vagina and higher in the area of the external genitalia. Progesterone receptors are found only in the vagina and the epithelium of the vulvovaginal junction [10]. Since the cells of the vaginal stroma contain estrogen receptors, collagen, which is part of the connective tissue of the vaginal wall, is an estrogen-sensitive structure, the content of which decreases as estrogen deficiency progresses. Since estrogen receptors are located not only in the epithelium and stroma of the vaginal wall, but also in the vascular endothelium, in postmenopause there is a decrease in blood circulation in the vagina to the level of varying degrees of ischemia. In addition, estrogens are vasoactive hormones that increase blood flow by stimulating the release of endothelial mediators such as nitric oxide, prostaglandins, and endothelial hyperpolarizing factor. Such a progressive decrease in blood flow in the vaginal mucosa leads to hyalinization of collagen and fragmentation of elastic fibers, increasing the amount of connective tissue [12].

Estrogen receptors have also been found on autonomic and sensory neurons in the vagina and vulva. A study by TL Griebling, Z. Liao, PG Smith revealed a decrease in the density of sensory nociceptive neurons in the vagina during estrogen treatment. This feature may be useful in addressing the discomfort associated with VA, namely in relieving symptoms such as burning, itching and dyspareunia that many postmenopausal women experience [5, 10].

Atrophy of the vulvar and vaginal mucosa is characterized by thinning of the epithelium, decreased vaginal folding, pallor, the presence of petechial hemorrhages, and signs of inflammation. Also, due to involutive changes, there is a loss of tissue elasticity, subcutaneous fat, loss of pubic hair, and a decrease in the secretory activity of the Bartholin glands [3, 13, 14]. Typically, doctors diagnose vulvar and vaginal atrophy based on a combination of clinical symptoms and visual examination. Researchers are increasingly insisting on more objective and reproducible diagnostic methods, without excluding subjective patient complaints [13]. Historically, to diagnose VA, two main objective methods of diagnosing and assessing the effectiveness of treatment are required: vaginal pH, as well as calculation of the vaginal maturation index (VII, the predominance of cells of the basal and parabasal layers) [12, 13]. Interestingly, the degree of atrophic changes, as measured by the maturation index, does not always correlate with symptoms [15]. In a study of 135 menopausal female volunteers who completed a symptom assessment followed by a rating of “vaginal health” (assessing vaginal color, discharge, epithelial integrity and thickness, pH) and a maturation index measurement, researchers found a weak correlation between physical symptoms and maturation index.

Hormonal changes that occur throughout the life cycle affect the vaginal flora from birth to postmenopause. A decrease in estrogen during perimenopause and postmenopause leads to a decrease in the number of lactobacilli and a change in flora in general. According to SL Hillier, RJ Lau, a detailed analysis of the vaginal microflora of 73 postmenopausal women who did not take hormonal therapy did not reveal lactobacilli in 49% of cases. And among those in whom they were detected, the concentration of the latter was 10–100 times less than in premenopausal women [15]. In postmenopause, the most common microorganisms were anaerobic gram-negative rods and gram-positive cocci.

Despite the above, some women experience wasting symptoms soon after menopause, while others do not experience them until later in life. Among the factors that may increase the risk of developing urogenital atrophy, smoking is one of the most studied. Smoking has a direct effect on the squamous epithelium of the vagina, reducing the bioavailability of estrogen and reducing blood perfusion. Other hormonal factors that tend to be important are the levels of various androgens such as testosterone and androstenedione. It has been suggested that after menopause, women with higher levels of androgens, which support sexual activity, have fewer changes associated with atrophy [12]. In addition, VA is observed more often in women who have never given birth vaginally [16].

Considering the pathogenesis of the disease, estrogen therapy is the gold standard of treatment. All clinical guidelines for the treatment of UGA agree that the most common and effective treatment method is systemic or local hormonal therapy with estrogen in various forms, as it quickly improves the maturation index and thickness of the vaginal mucosa, reduces vaginal pH and eliminates the symptoms of VA [ 3, 11–13]. To treat UGA combined with symptoms of menopause, systemic hormonal therapy is used. In other cases, local treatment is preferred, which avoids most systemic side effects [12, 13]. Studies have shown that systemic hormone replacement therapy eliminates symptoms of VA in 75% of cases, while local therapy eliminates symptoms in 80–90%.

Estrogen-containing preparations for local use, presented in the form of cream, tablets, pessaries/suppositories, vaginal ring, may contain estriol, conjugated equiestrogens, estradiol or estrone. Of the three natural estrogens in the human body, estriol has the shortest half-life and the least biological activity. In Russia, there is many years of experience in the local use of estriol-containing drugs that have a pronounced colpotropic effect. Given the weak proliferative effect on the endometrium when using estriol, additional administration of progestogen is not required. Numerous studies have shown that daily use of estriol at a dose of 0.5 mg has a noticeable proliferative effect on the vaginal epithelium. Local use of estriol-containing drugs is a safe and effective approach to the prevention and treatment of VA, which has no restrictions on age and duration of treatment. Currently, in European countries there is a trend towards local use of low doses of estrogens estriol and estradiol.

In 2006, a Cochrane systematic review analyzed 19 clinical trials involving 4,162 postmenopausal women, randomized to vaginal estrogen products, and evaluating the efficacy, safety, and acceptability of therapy as an endpoint. Fourteen studies compared the safety of different drugs, seven focused on side effects and four on treatment safety and effects on the endometrium. Seven studies included placebo groups, and all showed improvement in patients taking hormonal therapy (Table).

The results of the analysis show that vaginal estradiol tablets are more effective than the vaginal ring and that both treatments are superior to placebo in relieving dyspareunia, vaginal dryness and itching. Conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) vaginal cream is superior to moisturizing creams in relieving dryness and increasing elasticity and blood flow to the vagina. However, no differences were found between the three therapies analyzed (CLE cream, estradiol tablets, and estradiol-releasing ring) with respect to parabasal cell count, karyopyknotic index, maturation index, and vaginal health index. In addition, there are also reports of no significant differences in endometrial thickness, hyperplasia, and side effects between the vaginal ring, cream, or tablet. However, a slight risk of vaginal bleeding was described in all studies that used different methods of topical estrogen therapy, as well as a possible increased risk of candidiasis [16].

A meta-analysis by Cardozo et al showed that vaginal estrogen administration is an effective treatment for VA. The combination of local and systemic therapy allows you to achieve results in a shorter time. In addition, low doses of topical estrogens: estradiol or estriol are as effective as systemically administered ones. A transdermal patch with a daily dose of 14 μg of estradiol has been shown to have similar effects on vaginal pH and maturation index as a vaginal ring with 7.5 μg of estradiol [17].

The beneficial therapeutic effect of topical hormonal therapy has also been noted in situations beyond the treatment of VA, such as reducing the risk of recurrent urinary tract infections and the development of overactive bladder. Based on the above, the estradiol-releasing ring has been approved as a treatment for dysuria and urge urinary incontinence. While systemic hormonal therapy, on the contrary, increases the incidence of stress urinary incontinence and kidney stones [10].

Thus, local therapy has a number of advantages compared to systemic administration of drugs. It avoids primary metabolism in the liver, has minimal effects on the endometrium, has a low hormonal load, minimal side effects, does not require the addition of progestogens, and has a mainly local effect.

From a practical point of view, and due to the similar effectiveness and safety of all topical estrogen preparations, the patient should be able to choose the drug that she considers most suitable for her. She should be informed that the effect is achieved after one to three months of treatment. Additional administration of progestogens is not necessary when using local forms of estrogens [18]. A 2009 review of topical hormone therapy stated that no studies observed endometrial proliferation after 6 to 24 months of estrogen use, so the literature thus provides reassurance regarding the safety of low-dose vaginal preparations with estrogen and non-estrogens. supports the concomitant use of systemic progestogens to protect the endometrium [13].

In addition to the above treatment methods for VA, today there are such as therapy using dehydroepiandrosterone, selective tissue estrogen complexes, selective estrogen receptor modulators and non-hormonal treatment methods, as well as combination drugs containing ultra-low-dose estriol and lactobacilli.

In the work of U. Jaisamrarn et al. evaluated for the first time the efficacy and tolerability of ultra-low dose estriol (0.03 mg) in combination with viable Lactobacillus acidophilus in the short and long term for the treatment of symptoms of VA. It was found that the combination of estriol and lactobacilli for 12 weeks was sufficient to achieve statistically and clinically significant results, including improvement in objective parameters (VIS, pH, proportion of lactobacilli in the vaginal microflora), as well as the quality of life of women [19].

A large number of publications are devoted to the use of intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) gel for the treatment of VA [8]. DHEA is a sex hormone precursor that is produced by the adrenal glands and ovaries in addition to testosterone and estrogens. Subsequently, it undergoes biotransformation in peripheral tissues: in the brain, bones, mammary glands and ovaries. To date, specific receptors for DHEA have not been found, and therefore it is assumed that its action occurs through conversion to androgens and/or estrogens and interaction with their receptors, respectively. To date, most of the evidence for the beneficial effects of vaginally administered DHEA reported in five publications comes from a single randomized trial conducted by Labrie and colleagues. DHEA was used vaginally by 218 postmenopausal women for 12 weeks. Women were assigned to a placebo group taking 0.25% (3.25 mg), 0.5% (6.5 mg) or 1.0% (13 mg) vaginal cream daily. In patients receiving DHEA therapy, vaginal atrophy disappeared, while minimal changes in serum steroid hormone levels were observed, which remained within the normal range characteristic of postmenopause. Also in this study, there were positive effects on four aspects of sexual function: desire/interest, arousal, orgasm, and dyspareunia. DHEA 0.5% (6.5 mg) cream was found to be optimal for the treatment of vaginal atrophy and did not significantly affect serum estrogen levels [20].

Among the selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), ospemifene is the most advanced drug available. A 12-week, three-phase randomized trial involving 826 postmenopausal women examined the effectiveness of this drug at a dose of 30 mg, 60 mg compared with placebo. At weeks 4 and 12, ospemifene at the previously reported doses showed statistically significant increases in superficial cell counts, decreases in parabasal cells, and decreases in vaginal pH compared with placebo. Vaginal dryness was significantly reduced in both the 30 mg and 60 mg groups compared to placebo at week 12, while dyspareunia was reduced only in the 60 mg group. The study found that the side effect of hot flashes occurred in 9.6%, 8.3% and 3.4% of participants in the ospemifene 30 mg, 60 mg and placebo groups, respectively. Endometrial thickness from baseline to week 12 changed on average by 0.42 mm, 0.72 mm and 0.02 mm in participants in the above groups, respectively [21].

The combination of conjugated estrogens and the selective estrogen receptor modulator bazedoxifene, known as tissue selective estrogen complex (TSEC), was studied in a phase 3 study where 601 women were randomized to receive daily therapy: 20 mg bazedoxifene plus conjugated estrogens. .45 mg (BZA/CE), or bazedoxifene 20 mg plus 0.625 mg conjugated estrogens, or bazedoxifene 20 mg and placebo. The study found an increase in the proportion of superficial cells and a decrease in the proportion of parabasal cells from baseline to week 12, to a greater extent in the BZA/CE group compared with placebo and BZA alone. Vaginal pH did not change significantly from baseline to the end of the study in the BZA or placebo group, but decreased significantly in both BZA/CE groups. However, the decrease in vaginal pH was significantly lower in the BZA/CE 20 mg/0.625 mg group than in the placebo group. Most bothersome symptoms were significantly reduced by week 12 compared with placebo in the BZA/CE 20 mg/0.625 mg group, but not in the BZA/CE 20 mg/0.45 mg group. There were no significant differences in side effects or study discontinuations between groups. However, a higher incidence of vaginitis was noted in the treatment groups (BZA/CE) compared with placebo [22]. Thus, TSEC, namely bazedoxifene in combination with conjugated estrogens, represents an alternative to progestin therapy to protect the endometrium from estrogen stimulation while maintaining the beneficial effects of estrogen on menopause-related symptoms.

Despite the listed methods of treating VA, one should not forget about preventing the disease. Maintaining regular sexual activity is recommended in general for all women and in particular for menopausal women. This is because sexual intercourse improves blood circulation in the vagina, and seminal fluid also contains sex steroids, prostaglandins and essential fatty acids, which help maintain vaginal tissue [12].

Although the official prevalence of vaginal atrophy varies depending on the size and individual characteristics of the population studied, an increasing number of women are affected by this condition as the population ages. One study conducted by foreign colleagues showed that more than 60% of women experience symptoms of VA 4 years after postmenopause. However, only 4% of women aged 55–65 years associate the above complaints with vaginal atrophy, 37% know that these symptoms are reversible, and 75% of women believe that symptoms of VA negatively affect their lives. Given the sensitive nature of these symptoms, patients are hesitant to seek medical help and consequently suffer from progressive symptoms [10, 23]. Only 25% of women with symptoms of vaginal atrophy seek medical help. VA is a chronic and progressive condition [10]. A significant number of women with symptoms of VA do not even realize that effective treatment is possible. Timely informing patients about the causes of the above symptoms and the possibilities for eliminating them can quickly improve the condition of women and restore their interest in life and its quality. Thus, the problem of maintaining health and preventing diseases caused by aging has acquired particular importance in recent years. Due to its relevance, new drugs for the treatment of VA are currently being developed and introduced, which will allow an individualized approach to patient treatment.

Literature

- Vikhlyaeva E. M. Guide to gynecological endocrinology. M.: Medical Information Agency, 1997. pp. 227–360.

- Urogenital disorders in menopause (clinical presentation, diagnosis, hormone replacement therapy). dis. Dr. med. Sci. M., 1998.

- Santiago Palacios. Managing urogenital atrophy // Maturitas. 2009; 63:315–318.

- Sinha A., Ewies AAA Non-hormonal topical treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy: an up-to-date overview // Climacteric. 2013; 16: 305–312.

- Griebling TL, Liao Z., Smith PG Systemic and topical hormone therapies reduce vaginal innervation density in postmenopausal women // Menopause. 2012; 19: 630–635.

- Frank SM, Ziegler C., Kokot-Kierepa M., Maamari R., Nappi RE Vaginal Health: Insights, Views & Attitudes (VIVA) survey - Canadian cohort // Menopause Int. 2012.

- Rosano GMC, Vitale C., Silvestri A., Fini M. Metabolic and vascular effect of progestins in postmenopause // Maturitas. 2003; 46: 17–29.

- Hextall E. Esrogens in the funtion urethral tract // Maturitas. 2000; 36:83–92.

- Manukhin I. B., Tumilovich L. G., Gevorkyan M. A. Clinical lectures on gynecological endocrinology. M., 2003.

- Management of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy: 2013 position statement of The North American Menopause Society // The North American Menopause Society. 2013; 20(9):888–902.

- James H. Pickar. Emerging therapies for postmenopausal vaginal atrophy // Maturitas. 2013; 75:3–6.

- Camil Castelo-Branco, Maria Jes´us Cancelo, Jose Villero, Francisco Nohales, Maria Dolores Juli´a. Management of post-menopausal vaginal atrophy and atrophic vaginitis // Maturitas. 2005; 52:46–52.

- Sturdee DW, Panay N. Recommendations for the management of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy // Climacteric. 2010; 13:509–522.

- Basaran M., Kosif R., Bayar U., Civelek B. Characteristics of external genitalia in pre-and postmenopausal women // Climacteric. 2008; 11: 416–421.

- Paul Nyirjesy. Postmenopausal Vaginitis. Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2007; 9:480–484.

- Suckling J., Lethaby A., Kennedy R. Local oestrogen for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women // Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006.

- Gupta P., Ozel B., Stanczyk FZ, Felix JC, Mishell Jr. DR The effect of transdermal and vaginal estrogen therapy on markers of postmenopausal estrogen status // Menopause. 2008; 15(1)): 94–97.

- Pitkin J., Rees M. British Menopause Society Council. Urogenital atrophy // Menopause Int. 2008; 136–137.

- Jaisamrarn U., Triratanachat S., Chaikittisilpa S., Grob P., Prasauskas V., Taechakraichana N.. Ultra-low-dose estriol and lactobacilli in the local treatment of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy // Climacteric. 2013; 16: 347–355.

- Labrie F., Archer D.F., Bouchard C. et al. Intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (prasterone), a highly efficient treatment of dyspareunia // Climacteric. 2011; 14: 282–288.

- Bachmann GA, Komi JO The Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 study // Menopause. 2010; 17(3):480–486.

- Kagan R., Williams RS, Pan K., Mirkin S., Pickar JH A randomized, placebo-and active-controlled trial of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for treatment of moderate to severe vulvar/vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women // Menopause . 2010; 17(2):281–289.

- Kingsberg SA, Krychman ML Resistance and barriers to local estrogen therapy in women with atrophic vaginitis // J Sex Med. 2013; 1567–1574.

A. V. Glazunova S. V. Yureneva1, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor

FSBI NTs AGiP im. V. I. Kulakova Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Moscow

1 Contact information

Abstract. According to forecasts to 2030 there will be 1.2 bln women in postmenopause. The state of estrogen deficiency in climacterical period cause vaginal atrophy with 15–57% of women. The latest data on the problem of pathogenesis, clinical manifestations and therapy of this state are provided in review.

Causes

Atrophy is an acquired process in which tissues and organs dry out.

For general atrophy, the provoking factors are:

- oncological diseases;

- lack of nutrients;

- hypothalamic lesions;

- infectious diseases that occur over a long period of time;

- endocrine disorders.

The causes of local atrophy include:

- radiation exposure;

- pressure on an organ or part thereof;

- stress on muscles, limitation of physical activity;

- severe intoxication of the body due to serious infections;

- long-term use of hormonal drugs;

- innervation;

- circulatory disorders due to ischemic lesions of arteries and veins;

- heredity;

- dyshormonal disorders.

Indications

Treatment indications include:

- the presence of one or more symptomatic manifestations;

- head injuries or mechanical damage to the eye;

- regularly occurring headaches;

- dizziness, partial loss of vision;

- blurred vision;

- emerging eye fatigue.

If you have indications, you should contact a specialized center that will provide assistance. Don’t waste time, call our clinic and make an appointment with an ophthalmologist.

Diagnostics

In each specific case, diagnostic measures vary. At the initial stage, for any type of atrophy, the attending physician prescribes a physical examination, including anamnesis, palpation, visual examination and other procedures. In all cases, laboratory testing is necessary. Subsequent diagnosis is different. For example, to detect organ atrophy, ultrasound diagnostics, MRI or CT, radiography, scintigraphy, fibrogastroduodenoscopy and other procedures are performed. The main diagnosis of muscle atrophy is biopsy and electromyography. Laboratory diagnostics consists of assessing certain indicators in biochemical and general blood tests.

What are the possible consequences of atrophy?

Losing a tooth is not only fraught with cosmetic consequences, i.e. aesthetic defects. Functional impairments also occur. After all, healthy teeth have to take on excess load while chewing food. This means they break down much faster. In addition, all the teeth in the row shift and become mobile - after all, some of them lack lateral support. In general, the bite and facial expressions are disturbed, and wrinkles appear. The lips sink inside the mouth, problems arise with the pronunciation of various sounds, because the tongue loses support in the form of teeth, a decrease in the lower part of the face is observed, and flabbiness of the masticatory and facial muscles develops2. In addition, the digestive organs suffer, since a person most often switches to softer foods, since it is too difficult to chew excessively hard foods.

Options for solving the problem of bone loss

The main solution to the problem of bone loss is, of course, to prevent it, i.e. prevention. This means that after tooth extraction, you need to consider the option of surgical restoration or protecting the bone tissue from shrinkage. The first option will be discussed below, but the second involves the installation of protective barrier membranes. They are installed in the socket of the extracted tooth, and if necessary, a little artificial bone is added inside. In this way, it is possible to replenish the missing bone volume, making it possible to implant a tooth without using an extension procedure (but this is provided that it was not possible to install the implant immediately, i.e. at the time of tooth root removal).

So, when a patient is faced with a problem such as atrophy, bone tissue restoration can be performed using the following methods:

- sinus lift: performed exclusively on the upper jaw and allows you to lift or shift the maxillary sinus in order to make room for new bone. This operation is only applicable to change the height of the jaw bone,

- bone grafting with artificial materials: in this case, the jaw bone tissue is split and the freed space is filled with synthetic bone,

- bone block grafting method: for this procedure, the patient’s own bone material is used, usually extracted from the lower jaw (from the wisdom teeth area). The gum is cut, a bone block of the required size is cut out - it is transplanted to a new place and fixed with screws. Bone granules are placed around, and a membrane is attached to protect the tissue from being washed out.

Bone augmentation is a procedure that, although not complicated for an experienced surgeon, is very specific (and for the patient as well). When transplanting a bone block, at least 2 incisions are made, which means the patient will have to monitor the condition of several wounds at once. Plus additional material expenses: building up a large area of bone tissue is especially expensive.

“The cost of bone grafting is from 19-20 thousand rubles. And this does not take into account the implantation itself. In addition, the operation significantly lengthens the treatment process - at least 3-4 months must pass before the grafted bone can be used to install implants. Therefore, in our practice we use implantation methods that eliminate bone grafting. For the patient, this saves both time and money.”

Zhilenko Evgeniy Aleksandrovich, Implant surgeon, periodontist, orthopedist Work experience over 17 years make an appointment

Treatment

It is necessary to begin treatment by eliminating the underlying disease that provoked the appearance of the atrophic process. If sclerotic lesions and atrophy are not very advanced, it is possible to fully or partially restore the functions and structures of the affected organ or part thereof. However, deep atrophic lesions cannot be treated or corrected.

The specifics of treatment are influenced by the severity, form, duration of the disease, as well as the patient’s age and individual tolerance to medications. In each case, the doctor selects treatment methods individually. As a rule, long-term medication, physiotherapy and symptomatic treatment are prescribed. The course of treatment should not be interrupted and should be repeated regularly, taking into account the recommendations of the attending physician.

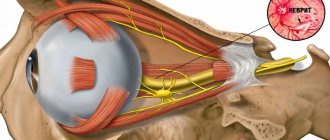

Treatment of partial optic atrophy

The principle of etiopathogenetic medicine requires the identification and maximum possible elimination of the causes of the disease; Since optic neuropathy is much more often a consequence and manifestation of other diseases than an autonomous and isolated pathology, the therapeutic strategy should begin with the treatment of the underlying disease.

In particular, for patients with intracranial (intracranial) oncological pathology, hypertension, established cerebral aneurysms, it is recommended, first of all, to undergo neurosurgical intervention in the appropriate direction.

Conservative treatment for optic nerve atrophy is focused on stabilizing and maintaining the functional status of the visual system to the extent possible in this particular case. Thus, various anti-edematous and anti-inflammatory measures may be indicated, in particular, retro- or parabulbar injections (administration of dexamethasone preparations, respectively, behind or next to the eyeball), droppers with solutions of glucose and calcium chloride, diuretics (diuretics, e.g. lasix). According to indications, injections of hemodynamic and optic nerve nutrition stimulants (trental, xanthinol nicotinate, atropine), intravenous nicotinic acid, aminophylline are also prescribed; vitamin complexes (B vitamins are especially important), aloe and vitreous extracts, tableted cinnarizine, piracetam, etc. For glaucomatous symptoms, medications that reduce intraocular pressure are used.

Fig.7 Medication, hardware and surgical methods can be used in the treatment of the disease

Physiotherapeutic methods such as acupuncture, laser or electrical stimulation, various modifications of the electrophoresis technique, magnetic therapy, etc. are quite effective for optic nerve atrophy.

An effective remedy is the INFRASOUND VACUUM OPHTHALMASSAGER AMBO-01, developed by Russian ophthalmologists under the guidance of Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor E.I. Sidorenko. specifically for patients with damage to the retina and optic nerve, which can improve vision by half[6]. The device is recommended for use both in a medical facility and at home. It is easy to use, has a low price and is delivered by the manufacturer throughout Russia.

MORE ABOUT AMBO-01 ON THE MANUFACTURER'S OFFICIAL WEBSITE>>>

There is also a surgical treatment for atrophic conditions - this is a procedure for revascularization of the posterior part of the eye. Its essence boils down to the movement “on a stalk” of the external oculomotor muscles or areas of the sclera from the lateral surface to the posterior pole of the eye to the central zone of the retina (macula) and the optic nerve. Blood vessels move along with them to provide additional nutrition to the nerve.

Fig. 8 Scheme of surgical treatment of PAI

During revascularization, various additives can be used: drugs “Retinalamin”, “Aminion”, components of the patient’s own blood (plasma or cells), etc. The operation gives high results not only in stabilizing the process, but also increases visual acuity and fields, especially in combination with drug and cell therapy.[7]

MORE ABOUT REVASCULARIZATION >>>