Paroxysmal disorders of consciousness in neurology are a pathological syndrome that occurs as a result of the course of the disease or the body’s reaction to an external stimulus. Disorders manifest themselves in the form of attacks (paroxysms) of various types. Paroxysmal disorders include migraine attacks, panic attacks, fainting, dizziness, epileptic seizures with and without convulsions.

Neurologists at the Yusupov Hospital have extensive experience in treating paroxysmal conditions. Doctors know modern effective methods for treating neurological pathologies.

Disorder of consciousness

Paroxysmal disorder of consciousness manifests itself in the form of neurological attacks. It can occur against the background of apparent health or during an exacerbation of a chronic disease. Often, paroxysmal disorder is recorded during the course of a disease that is not initially associated with the nervous system.

The paroxysmal state is characterized by the short duration of the attack and the tendency to recur. The disorder has different symptoms, depending on the provoking condition. Paroxysmal disorder of consciousness can manifest itself as:

- epileptic seizure,

- fainting,

- sleep disorder,

- panic attack,

- paroxysmal headache.

The causes of the development of paroxysmal conditions can be congenital pathologies, injuries (including at birth), chronic diseases, infections, and poisoning. Patients with paroxysmal disorders often have a hereditary predisposition to such conditions. Social conditions and harmful working conditions can also cause the development of pathology. Paroxysmal disorders of consciousness can cause:

- bad habits (alcoholism, smoking, drug addiction);

- stressful situations (especially when they are repeated frequently);

- disturbance of sleep and wakefulness;

- heavy physical activity;

- prolonged exposure to loud noise or bright light;

- unfavorable environmental conditions;

- toxins;

- sudden change in climatic conditions.

Terminology and related concepts

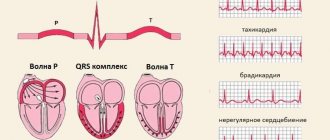

In adults (after 21 years), bioelectrical activity of the brain (BEA) should normally be synchronous, rhythmic and not have foci of paroxysms. In general, paroxysm is an intensification to the maximum of any pathological attack or (in a narrower sense) its recurrence. In this case, paroxysmal brain activity means that:

- when measuring the electrical activity of the cerebral cortex using EEG, it is discovered that in one of the areas the processes of excitation prevail over the processes of inhibition;

- the process of excitation is characterized by a sudden onset, transience and sudden ending.

In addition, when checking the state of the brain on an EEG, patients develop a specific pattern in the form of sharp waves that very quickly reach their peak. Pathologies can be observed in different rhythms: alpha, beta, theta and delta rhythms. In this case, additional characteristics can suggest or diagnose the disease. When deciphering and interpreting the EEG, clinical symptoms and general indicators must be taken into account:

- basal rhythm,

- the degree of symmetry in the manifestation of electrical activity of neurons of the right and left hemispheres,

- changing schedules during functional tests (photostimulation, alternating closing and opening of eyes, hyperventilation).

Alpha rhythm

The norm for alpha frequency in healthy adults is 8-13 Hz, amplitude fluctuations are up to 100 μV. Alpha rhythm pathologies include:

- Paroxysmal rhythm, which, as well as weak expression or weak activation reactions in children, may indicate a third type of neuroses.

- Interhemispheric asymmetry exceeding 30% may indicate a tumor, cyst, manifestations of a stroke, or a scar at the site of a previous hemorrhage.

- Disruption of sine waves.

- Unstable frequency - allows you to suspect a concussion after a head injury.

- A permanent shift of the alpha rhythm to the frontal parts of the brain.

- Extreme amplitude values (less than 20 µV and more than 90 µV).

- Rhythm index with a value less than 50%.

Beta rhythm

During normal brain function, it is most pronounced in the frontal lobes. It has a symmetrical amplitude of 3-5 µV. Pathologies are recorded when:

- paroxysmal discharges,

- interhemispheric asymmetry in amplitude above 50%,

- increasing the amplitude to 7 μV,

- low-frequency rhythm along the convexital surface,

- sinusoidal graph.

In this list, a concussion is indicated by diffuse (non-localized) beta waves with amplitudes of up to 50 μV. Encephalitis is indicated by short spindles, the frequency, duration and amplitude of which are directly proportional to the severity of inflammation. For psychomotor delay in the development of a child - high amplitude (30-40 μV) and frequency of 16-18 Hz.

Theta and delta rhythms

These rhythms are normally recorded in sleeping people, but when they occur in people who are awake, they speak of dystrophic processes developing in the brain tissue and associated with high pressure and compression. At the same time, the paroxysmal nature of theta and delta waves indicates deep brain damage. Until the age of 21, paroxysmal discharges are not considered a pathology. But if a disorder of this nature is recorded in adults in the central parts, then acquired dementia can be diagnosed. This can also be evidenced by flashes of bilaterally synchronous high-amplitude theta waves. In addition, paroxysms of these waves also correlate with the third type of neuroses.

Summarizing all paroxysmal manifestations, two types of paroxysmal conditions are distinguished: epileptic and non-epileptic.

Epileptic type of paroxysmal activity

A pathological condition characterized by convulsions and seizures, sometimes repeated one after another, is epilepsy. It can be congenital or acquired as a result of traumatic brain injury, tumors, acute circulatory disorders, or intoxication. Another classification of epilepsy is based on the localization factor of the paroxysmal focus that provokes seizures. Epileptic seizures, in turn, are also divided into convulsive and non-convulsive with a wide typological spectrum.

Grand mal seizure

This type of seizure is most common in epilepsy. Several phases are observed during its course:

- aura,

- tonic, clonic phases (atypical forms),

- confusion (twilight disorder or stupor).

1. An aura is a short-term (counted in seconds) clouding of consciousness, during which the surrounding events are not perceived by the patient and are erased from memory, but hallucinations, affective, psychosensory, depersonalization facts are remembered.

Some researchers (for example, W. Penfield) believe that the aura is an epileptic paroxysm, and the subsequent grand mal seizure is a consequence of the generalization of excitation in the brain. The clinical manifestations of the aura are used to judge the localization of foci and the spread of excitation. Among several classifications of the aura, the most common division is into:

- viscerosensory - begins with nausea and an unpleasant sensation in the epigastric zone, continues with an upward displacement, and ends with a “blow” to the head and loss of consciousness;

- visceromotor - manifests itself in a variety of ways: sometimes - dilation and contraction of the pupil not associated with changes in lighting, sometimes - alternating skin redness and heat with paleness and chills, sometimes - “goose bumps”, sometimes - diarrhea, pain and rumbling in the abdomen;

- sensory – with various manifestations of auditory, visual, olfactory and other characters, dizziness;

- impulsive – manifested by a variety of motor acts (walking, running, violent singing and shouting), aggression towards others, episodes of exhibitionism, kleptomania and pyromania (an attraction to arson);

- mental - where the hallucinatory type manifests itself in visual hallucinations of scenes of holidays, manifestations, disasters, fires in bright red or blue tones, in olfactory and verbal hallucinations, and the ideational type of mental aura - in the form of a thinking disorder (reviews of survivors describe it as “blockage of thoughts ", "mental blocker").

The last, mental, type of aura also includes deja vu (deja vu - the feeling of what has already been seen) and jamais vu (jamais vu - the opposite feeling of never seen, although objectively familiar).

It is important that these disorders fall under the definition of “aura” only if they become precursors to the generalization of a seizure. The transition from an aura to a grand mal seizure occurs without an intermediate stage. If the stage of a convulsive seizure does not occur, then these disorders are classified as independent nonconvulsive paroxysms.

2. Rudimentary (atypical) forms of a grand mal seizure are possible in the form of tonic or clonic phases. Such forms are typical when manifested in early childhood. Sometimes their manifestation is expressed in non-convulsive relaxation of the body muscles, sometimes with a predominance of spasms in the left or right part of the body.

3.

Epileptic state (status) . A dangerous condition that, if prolonged, can lead to the death of the patient due to increasing hypoxia or cerebral edema. Before this, status epilepticus may be accompanied by somatovegetative symptoms:

- temperature rise,

- increased heart rate,

- a sharp decrease in blood pressure,

- sweating, etc.

In this status, seizures of 30 minutes or more follow each other, and this sometimes lasts up to several days, so that the patients do not regain consciousness, being in a stunned, comatose and stuporous state. At the same time, the concentration of urea in the blood serum increases, and protein appears in the urine. Each subsequent paroxysm occurs even before the disturbances after the previous attack have time to subside. Unlike a single seizure, in the case of status epilepticus the body is not able to stop it. For every 100 thousand people, status epilepticus occurs in 20.

Minor seizures

The clinical manifestation of minor seizures is even wider than that of major seizures, which introduces significant confusion in their definition. This is also facilitated by the fact that representatives of different schools of psychiatry put different clinical content into the basic concept. As a result, some consider only those that have a convulsive component to be minor seizures, while others derive a typology that includes:

- typical – absence seizures and pycnoleptic – petit mal seizures,

- impulsive (myoclonic), and retropulsive,

- akinetic (which includes pecks, nods, atonic-akinetic and salam seizures).

- Absence seizures are conditions associated with a short-term sudden loss of consciousness. This may look like an unexpected interruption in conversation in the middle of a sentence, or an action "in the middle" of the process, the gaze begins to wander or stops, and then the process continues from the point of interruption. Sometimes, at the time of an attack, the tone of the muscles of the neck, face, shoulders, arms changes, and sometimes mild bilateral muscle twitching and autonomic disturbances occur. As a rule, such seizures end by age 10 and are replaced by grand mal seizures.

- Impulsive (myoclonic) seizures. They manifest themselves as unexpected shuddering with jerky movements of the hands, bringing them together and spreading them apart, in which a person cannot hold objects. In the case of a longer seizure, consciousness turns off for a few seconds, but quickly returns and, if a person falls, he quickly gets to his feet on his own. The basis of such movements, which can be repeated in “volleys” of 10-20 for several hours, is the “anti-gravity reflex” - exaggerated straightening.

differs in specific movements directed forward (propulsion). The resulting movement of the torso or head is explained by a sharp weakening of postural muscle tone. It occurs more often at night in boys under 4 years of age. Later, large convulsive seizures appear along with them. At the same time, nodding and pecking - sharp tilts of the head forward and down - are more typical for children under 5 months. Another type - Salaam seizures - got their name by analogy with the position of the arms, body and head, which are characteristic of a person bowing in a Muslim greeting.

Akinetic (propulsive) type

One person never experiences seizures of different clinical natures or a transition from one type to another.

Focal seizures

This epileptic form has three types:

- Adversive convulsive . It is distinguished by a specific rotation of the body around its axis: the eyes turn, followed by the head, and behind it the whole body, after which the person falls. The epileptic focus in this case is located in the anterior temporal or frontal region. However, if the paroxysmal focus is in the left hemisphere, the fall occurs more slowly.

- Partial (Jacksonian) . It is distinguished from the classic manifestation by the fact that the tonic and clonic phases affect only certain muscle groups. For example, a spasm moves from the hand to the forearm and further to the shoulder, from the foot to the lower leg and thigh, from the muscles near the mouth to the muscles of the side of the face where the spasm began. If generalization of such a seizure occurs, it ends in loss of consciousness.

- Tonic postural cramps . When paroxysmal activity is localized in the brainstem, powerful convulsions immediately begin, ending in breath-holding and loss of consciousness.

Nonconvulsive forms of paroxysms

Paroxysms associated with clouding of consciousness, twilight states, dream delirium with a fantastic plot, as well as forms without a disorder of consciousness (narcoleptic, psychomotor, affective paroxysms) are also quite widespread and varied.

– short-term twilight states of paroxysmal nature. A person performs automatic actions, completely detaching himself from the world around him. These can be actions associated with chewing, swallowing, licking (oral automatisms), rotating in place (rotatory automatisms), attempts to shake off “dust”, methodical undressing, running in an uncertain direction (so-called “fugues”). Sometimes aggressive, antisocial behavior is observed with simultaneous complete detachment from the environment.

Outpatient automatisms- Dream (special) states. They appear as dream-like delirium. With them there is no complete amnesia - the person remembers his visions, but does not remember the surrounding environment.

Epilepsy disorders

In epilepsy, paroxysmal conditions can manifest themselves in the form of convulsive seizures, absence seizures and trances (non-convulsive paroxysms). Before a grand mal seizure occurs, many patients feel a certain type of warning sign - the so-called aura. There may be auditory, auditory and visual hallucinations. Someone hears a characteristic ringing or feels a certain smell, feels a tingling or tickling sensation. Convulsive paroxysms in epilepsy last several minutes and may be accompanied by loss of consciousness, temporary cessation of breathing, involuntary defecation and urination.

Nonconvulsive paroxysms occur suddenly, without warning. With absence seizures, a person suddenly stops moving, his gaze is directed ahead, he does not react to external stimuli. The attack does not last long, after which mental activity returns to normal. The attack goes unnoticed by the patient. Absence seizures are characterized by a high frequency of attacks: they can be repeated tens or even hundreds of times per day.

Panic disorder (episodic paroxysmal anxiety)

Panic disorder is a mental disorder in which the patient experiences spontaneous panic attacks. Panic disorder is also called episodic paroxysmal anxiety disorder. Panic attacks can occur from several times a day to once or twice a year, while the person is constantly expecting them. Severe anxiety attacks are unpredictable because their occurrence does not depend on the situation or circumstances.

This condition can significantly impair a person's quality of life. The feeling of panic can be repeated several times a day and last for an hour. Paroxysmal anxiety can occur suddenly and cannot be controlled. As a result, a person will feel discomfort while in society.

The clinical picture of cerebral paroxysms of both epileptic and non-epileptic origin is distinguished by a variety of manifestations, which sometimes leads to diagnostic errors and the prescription of inadequate therapy. It should be remembered that overdiagnosis of epilepsy in the long term can cause no less harm to the patient than missed cases. Most diagnostic errors can be avoided thanks to a careful and detailed collection of anamnestic information, a competent approach to monitoring the patient and an adequate assessment of instrumental examination methods. The case we describe demonstrates the polymorphism of paroxysmal states in childhood.

Clinical case

Patient V. , was admitted to the neurological department of the 3rd City Children's Clinical Hospital in Minsk at the age of 1 year 6 months with complaints of episodic “rolling” of the eyes to the side for several seconds, while at the time of this paroxysm the child had no reaction to treatment or sound stimuli . Similar conditions were noted by the girl’s mother within a week before admission to the hospital. The disease began with 2 episodes during the day, then the number of paroxysms increased to 10–15 times. The mother denied any previous traumatic damage to the central nervous system; The child also had no previous history of traumatic brain injuries, disturbances of consciousness, or paroxysmal states of epileptic or non-epileptic origin.

From the anamnesis: a child from the 2nd pregnancy, first term birth. Delivery was carried out by vacuum extraction at 41 weeks of gestation. The pregnancy proceeded against the background of the threat of termination due to acute respiratory viral infections in the 1st and 2nd trimesters. Birth weight was 3,810 g, length 51 cm. Artificial feeding. The child's development before hospitalization corresponded to the age norm, vaccinations were completed. During the previous period, the child suffered only colds. The mother denied chronic somatic pathology and surgical interventions. Heredity and transfusion history were not burdened, but the girl had an allergic pathology (food allergy to cow's milk protein).

On admission, the somatic status was unremarkable. Physical development is average, disharmonious in weight. Neurological status: the girl is conscious, emotionally labile, adequate in behavior, accessible for examination and age-appropriate contact. The dream, according to the mother, is calm. On the part of the cranial nerves, slight asymmetry of the nasolabial folds was noted. Upper limbs: range of motion and physiological muscle tone. Muscle strength is age appropriate. Muscle trophism without features. There is no hyperkinesis. SPR D=S, revived, reflexogenic zones are not expanded. Abdominal reflexes D=S, medium alertness. Lower limbs: physiological range of motion. Muscle strength is age appropriate. Muscle trophism without features. Muscle tone is closer to physiological, slightly increased. There is no hyperkinesis. Knee reflexes D=S, Achilles reflexes D=S. There are no pathological foot signs. Coordination sphere without features. He has been walking independently since the age of 1 year 1 month, slightly internally rotating the right foot, with a tendency to place weight on the forefoot (episodic benign dystonic reaction of weight bearing on the foot). There are no meningeal symptoms. Pelvic organs without pathology.

On the second day of stay in the department, the number of episodes of eye movement to the side was about 10. The duration of the episodes ranged from 5–10 seconds to several minutes. Episodes of eye aversion were accompanied by mild coordination disorder, which disappeared 5–10 minutes after the end of the oculomotor paroxysm.

A preliminary diagnosis was made: paroxysmal conditions with the presence of episodes of tonic abduction of the eyes towards an unspecified genesis.

Before the examination, in order to reduce the excitability of the central nervous system, the child was prescribed gromecin at a dose of 0.1 g, 1 tablet 2 times a day.

An electroencephalographic (EEG) examination revealed mild diffuse changes with signs of neurophysiological immaturity. No paroxysmal activity was recorded (see Fig. 1). General and biochemical blood tests without pathology.

Figure 1. Initial EEG examination. Mild diffuse changes with signs of neurophysiological immaturity. A neuroimaging study (MRI 2 T) revealed signs of a slight increase in the MR signal in the parahippocampal region ( see Fig. 2a ) and a slight expansion of the anterior subarachnoid space ( see Fig. 2b ), which may testify in favor of hypoxic-ischemic perinatal encephalopathy. On the third day, the number of episodes of eye aversion decreased to 6, while their duration did not exceed several seconds.

Figure 2a. MRI study. Signs of increased MR signal in the parahippocampal region.

Figure 2b. MRI study. Signs of a slight expansion of the anterior subarachnoid space. On the fourth day, the number of paroxysms continued to decrease and amounted to only 2 episodes lasting 1–2 seconds. At the same time, no coordination impairments accompanying these conditions were previously noted.

On the fifth day, the episodes of eye aversion completely stopped and did not recur on subsequent days in the hospital.

Repeated EEG examinations carried out on the third and sixth ( see Fig. 3a, 3b ) days from the moment of hospitalization did not reveal regional and pathological forms of bioelectrical activity.

A blood test for viruses, bacteria and protozoa did not reveal a significant infectious factor in the development of the current disease.

Figure 3a. Repeated EEG examination. Mild diffuse changes in the bioelectrical activity of the brain. No regional or pathological forms of activity were identified.

Figure 3b. Repeated EEG examination. Mild diffuse changes in the bioelectrical activity of the brain. No regional or pathological forms of activity were identified.

The final diagnosis: paroxysmal conditions of the type of benign episodes of tonic abduction of the eyes towards non-epileptic origin.

Antiepileptic therapy was not prescribed. The child was discharged home in satisfactory condition.

During a follow-up examination 2 months after discharge from the hospital, it was found that paroxysmal conditions did not recur, and the neurological status remained the same. The girl has advanced in psycho-speech development: her active and passive vocabulary has increased, and she began to speak in two-word sentences. An EEG examination did not reveal any significant changes.

A comment

Benign tonic eye deviations in children are a heterogeneous group of conditions with prolonged episodes of permanent or transient deviations of the eyeballs in the opposite direction to the desired direction with a rapid return to the original position.

The etiology of the described paroxysmal condition is heterogeneous, and the pathogenesis remains not fully established to this day. According to the results of studies by some authors, the disease can have an autosomal recessive and autosomal dominant nature of inheritance. Such patients may have mutations in the calcium channel gene CACNA1A. It is impossible to exclude the possibility of the functional genesis of benign tonic abduction of the eyes to the side due to the immaturity of brain structures and disruption of interneuronal communication.

Most often, researchers consider the hypothesis of age-dependent dysfunction of supranuclear pathways. The etiological factors of symptomatic forms of the disease can be damage to the mesencephalic region - malformation of the vein of Galen, pinealoma, hydrocephalus, pituitary tumor. The iatrogenic nature of this paroxysmal state is also possible. A number of authors indicate its more frequent development in those children whose mothers took valproic acid drugs during pregnancy.

Clinical manifestations of benign tonic eye abduction to the side are somewhat varied. The onset of the disease usually occurs at the age of 4–10 months. In the largest study of this pathology, the age of onset varied from 1 week to 26 months of life (average 5.5 months). The frequency of attacks varies throughout the day from single to hourly. Characteristic is the increase in frequency and severity of paroxysms in infectious diseases accompanied by fever, as well as in physical and psycho-emotional fatigue. As a rule, during the entire period of the disease, no modification of the type of paroxysms occurs. It is believed that the duration of the disease and the time to achieve remission (spontaneous disappearance of the abduction of the eyes) on average can vary from several days to 5 years.

With benign tonic abduction of the eyes to the side and upward, a number of children experience episodes of additional downward tilt of the chin, but a number of authors believe that this is a compensatory mechanism to correct the incorrect position of the eyeballs. With the existing stereotype of moving the eyes in a certain direction, the opposite movement is usually not changed. However, in some patients, unidirectional nystagmus with a fast component in the opposite direction may occur during paroxysm.

In addition, some researchers have described hypometric saccades and divergent strabismus, which can persist for some time (in some cases for a long time) after the cessation of tonic abduction of the eyes.

The described non-epileptic paroxysmal state is periodically accompanied by motor clumsiness and ataxia of varying severity, lasting from several hours to several days. Mild coordination dysfunction may also tend to persist after resolution of the underlying disease.

According to various authors, about 50% of children with benign tonic abduction of the eyes to the side have normal mental development, approximately 40% have a mild intellectual deficit, 10% have moderate to severe intellectual impairment. In the vast majority of cases, normal psychoneurological status in patients with the described variant of paroxysms correlates with spontaneous remission within 2 years from the onset of the disease. If there is a combination of this condition and a neurological and/or cognitive-mnestic deficit, then an additional examination of the child is necessary for the symptomatic nature of the etiology of the pathological process.

Instrumental diagnostic and laboratory studies most often demonstrate normal neuroimaging, electroencephalography and metabolic parameters of blood and cerebrospinal fluid in children with idiopathic (genetic) forms of the disease. The gold standard for neuroimaging examination, MRI of the brain, usually does not reveal pathological changes.

The differential diagnosis of benign tonic eye deviations to the side is carried out with epileptic paroxysmal conditions, in particular with oculomotor seizures and atypical absences.

Specific treatment for this condition has not been developed; attempts at therapeutic intervention are most often ineffective. According to the largest study, therapy with anticonvulsants, acetazolamide and adrenocorticotropic hormone had no effect on the course of the disease. Nevertheless, a number of authors indicate the achievement of a positive effect in relation to the frequency and severity of paroxysms with the use of dihydroxyphenylalanine (levodopa).

Sleep disorders

The manifestations of paroxysmal sleep disorders are very diverse. These may include:

- nightmares;

- talking and screaming in sleep;

- sleepwalking;

- motor activity;

- night cramps;

- shuddering when falling asleep.

Paroxysmal sleep disorders do not allow the patient to regain strength or rest properly. After waking up, a person may feel headaches, fatigue and weakness. Sleep disorders are common in patients with epilepsy. People with this diagnosis often have realistic, vivid nightmares in which they run somewhere or fall from a height. During nightmares, your heart rate may increase and you may perspire. Such dreams are usually remembered and can be repeated over time. In some cases, during sleep disorders, breathing disturbance occurs; a person may hold his breath for a long period of time, and there may be erratic movements of the arms and legs.

Treatment

To treat paroxysmal conditions, consultation with a neurologist is necessary. Before prescribing treatment, the neurologist must know exactly the type of attacks and their cause. To diagnose the condition, the doctor clarifies the patient’s medical history: when the first episodes of attacks began, under what circumstances, what their nature is, and whether there are any concomitant diseases. Next, you need to undergo instrumental studies, which may include EEG, EEG video monitoring, MRI of the brain and others.

After performing an in-depth examination and clarifying the diagnosis, the neurologist selects treatment strictly individually for each patient. Therapy for paroxysmal conditions consists of medications in certain doses. Often the dosage and the drugs themselves are selected gradually until the required therapeutic effect is achieved.

Typically, treatment of paroxysmal conditions takes a long period of time. The patient should be constantly monitored by a neurologist for timely adjustment of therapy if necessary. The doctor monitors the patient’s condition, assesses the tolerability of the drugs and the severity of adverse reactions (if any).

The Yusupov Hospital has a staff of professional neurologists who have extensive experience in treating paroxysmal conditions. Doctors are proficient in modern effective methods of treating neurological pathologies, which allows them to achieve great results. The Yusupov Hospital performs diagnostics of any complexity. Using high-tech equipment, which facilitates the timely start of treatment and significantly reduces the risk of complications and negative consequences.

The clinic is located near the center of Moscow and receives patients around the clock. You can make an appointment and get advice from specialists by calling the Yusupov Hospital.

Non-epileptic paroxysmal states

Such conditions can be divided into four forms:

- Muscle dystonic syndromes (dystonia).

- Myoclonic syndromes (this also includes other hyperkinetic states).

- Autonomic disorders.

- Headache.

They are associated with a neurological nosology that occurs at a young age. But the syndromes characteristic of these conditions appear for the first time or progress also in adults and older people. The worsening of the condition in this case is associated with both chronic cerebral circulatory disorders and age-related cerebral disorders.

In this regard, to prevent such paroxysmal conditions, it would be logical to use drugs that provide blood supply to the brain and activate microcirculation. However, the quality of the effects of such drugs can play a decisive role in their choice, since non-epileptic paroxysmal states are often the result of increased long-term use of medications that compensate for the lack of blood circulation.

Therefore, it is assumed that prophylactic agents that improve blood circulation

- firstly, they must affect the brain not immediately and not constantly, but through a course of accumulation of active substances (after which a break is taken in taking the drug),

- secondly, they should have a “mild” non-aggressive effect without pronounced side effects, subject to the recommended

dosages.

These requirements are met by natural herbal preparations, the components of which, in addition to activating cerebral circulation, strengthen the walls of blood vessels, reduce the risk of blood clots, and reduce the adhesion of red blood cells. Among the most popular in this series are the natural remedy “HeadBuster”, the natural “Optimentis” with the addition of vitamins - both complexes based on (or with the inclusion of) extracts of ginkgo and ginseng.

Dystonia

The conditions are manifested by periodic or constant muscle spasms, which force the person to assume “dystonic” postures.” The distribution of hyperkinesis across muscle groups, together with the degree of generalization, allows us to divide dystonia into 5 forms:

- Focal. The muscles of only one part of the body are involved, subdivided into blepharospasm, writer's cramp, foot dystonia, spasmodic torticollis, and oromandibular dystonia.

- Segmental. Two adjacent parts of the body are involved (muscles of the neck and arms, legs and pelvis, etc.).

- Hemidystonia. The muscles of one half of the body are involved.

- Generalized. Affects muscles throughout the body.

- Multifocal. Affects two (or more) non-contiguous areas of the body.

Typical dystonic postures and syndromes may have a “telling” name, which in itself describes the human condition: “belly dance”, “ballerina’s foot”, etc.

The most common form of dystonia is spasmodic torticollis. This syndrome is characterized by disturbances when trying to hold the head in an upright position. The first manifestations occur at the age of 30-40 and are more often (one and a half times) observed in women. A third of cases are in remission. This form is very rarely generalized, but can be combined with other types of focal dystonia.

Myoclonic syndromes

Myoclonus is a jerky short tremor of the muscles, similar to a contraction reaction during a single electrical discharge that irritates the corresponding nerve. The syndrome can involve several muscle groups at once, sometimes leading to complete generalization, or it can be limited to one muscle. Jerks of this kind (jerks) can be synchronous or asynchronous. Most of them are arrhythmic. Sometimes they are very strong and sharp, which leads to a person falling. Myoclonus has been described that depends on the sleep-wake cycle.

Based on the location parameter in the nervous system of the generation of myoclonic discharges, 4 types are distinguished:

- cortical,

- stem,

- spinal,

- peripheral.

Other hyperkinetic syndromes

Manifest in the form of episodes of muscle cramps and tremors. According to clinical manifestations, they are between myoclonus and muscular dystonia, resembling both.

Cramps here are spontaneous (or occurring after exercise) painful involuntary muscle contractions in the absence of the antagonistic regulatory influence of the opposing muscles. Non-parkinsonian tremor manifests itself in tremulous hyperkinesis that occurs during movement.

Headache

The statistical frequency of headaches is estimated at 50-200 cases per 1000 people, being the leading syndrome in fifty different diseases. There are several classifications of it. In Russia, the pathogenetic one (V.N. Shtoka) is better known, where 6 basic types are distinguished:

- vascular,

- muscle tension,

- neuralgic,

- liquorodynamic,

- mixed,

- central (psychalgia).

The international classification includes migraine (without aura and associated), cluster pain, infectious, tumor, cranial, etc. Some headaches (for example, migraine) appear both as an independent disease and as an accompanying symptom of some other diseases. Migraine, cluster pain and tension headaches are of a psychogenic nature and are characterized by paroxysmal course.

Autonomic disorders

In the context of autonomic dystonia syndrome, the following groups of autonomic disorders are distinguished:

- psycho-vegetative syndrome,

- vegetative-vascular-trophic syndrome,

- syndrome of progressive autonomic failure.

The first group is more common and is expressed in emotional disorders with parallel vegetative disorders of a permanent and/or paroxysmal nature (pathologies of the gastrointestinal tract, thermoregulation, breathing, cardiovascular system, etc.). The most obvious illustrations of violations of this group include:

panic attacks (in 1-3% of people, but 2 times more often in 20-45 year old women) and neurogenic syncope (frequency up to 3%, but the percentage increases to 30% at puberty).