Viral and bacterial meningitis

MGMSU named after N.A. Semashko Meningitis is a group of diseases characterized by damage to the meninges and inflammatory changes in the cerebrospinal fluid.

Normal number of cells in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

is no more than 5 in 1 µl [1, 2], the amount of protein is no more than 0.45 mg/l, sugar is no less than 2.2 mg/l. Cells in normal cerebrospinal fluid are represented by lymphocytes.

According to the composition of the formed elements in the cerebrospinal fluid and etiology, meningitis is divided into purulent

(bacterial) with a predominance of neutrophilic leukocytes and

serous

(usually viral) with predominantly lymphocytic pleocytosis.

Some bacterial meningitis is characterized by a predominance of the lymphocytic (serous) composition of the cerebrospinal fluid (tuberculosis, syphilitic, Lyme borreliosis, etc.). Meningitis can be primary

or

secondary

(develops against the background of an existing general or local infectious process);

according to the nature of the course - acute

,

chronic

, sometimes fulminant.

In pathogenesis

Meningitis is played by a complex of factors: first of all, the properties of the pathogen, the reaction of the host organism and the background against which the contact of the micro- and macroorganism occurs. The virulence of the pathogen, its neurotropism and other features are of great importance. In the host’s reaction, a significant role is played by age, nutrition, social factors, previous injuries and diseases, the nature of previous treatment, immune status, etc. Environmental conditions include exposure to physical factors of cooling, overheating, insolation; contacts with animals, vectors and sources of infection, etc.

Certain individuals have an increased risk of developing infections of the nervous system. These include people with certain concomitant diseases and chronic infections, such as skull injuries, consequences of neurosurgical interventions and shunting of the cerebrospinal fluid system, chronic purulent processes in the chest cavity, septic endocarditis, lymphoma, blood diseases, diabetes, chronic diseases of the paranasal sinuses, alcoholism, long-term therapy with immunosuppressants, etc. The high-risk group also includes patients with congenital and acquired immune defects, pregnant women, patients with unrecognized diabetes, etc. In such individuals, due to a defect in immune defense, there is an increased risk of viral infections that they have already encountered in early childhood. This primarily includes diseases caused by the herpes group: cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, varicella-zoster virus.

The pathogen can penetrate into the meninges in various ways: hematogenous, lymphogenous, perineural or contact (in the presence of a purulent focus in direct contact with the meninges - otitis media, sinusitis, brain abscess).

Overproduction of CSF, disruption of intracranial hemodynamics, and the direct toxic effect of the pathogen on the brain substance are essential in the pathogenesis of meningitis. The permeability of the blood-brain barrier increases, the endothelium of the brain capillaries is damaged, microcirculation is disrupted, and metabolic disorders develop, aggravating brain hypoxia. As a result, cerebral edema occurs, the progression of which can lead to brain dislocation and death from respiratory and cardiac arrest [3].

Viral meningitis

The etiological classification of viral meningitis most fully meets epidemiological and practical requirements. Most authors consider enteroviral meningitis to be one of the most common types of viral meningitis [4, 5]. The genus of enteroviruses (family Picornaviridae) includes poliovirus types 1–3, Coxsackie viruses A (types 1–24) and B (types 1–6), ECHO viruses (types 1–34), enteroviruses 68 -71st types. All representatives of enteroviruses cause meningitis, but most often the Coxsackie and ECHO viruses. Often the causes of viral meningitis are also paramyxoviruses (mumps, parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial), viruses of the herpes family (herpes simplex type 2, varicella-zoster, Epstein-Barr, herpes virus type 6), arboviruses (tick-borne encephalitis) , lymphocytic choriomeningitis, etc.

Clinic

Meningitis, including viral ones, is characterized by an acute onset with high fever, headache, nausea and vomiting, general malaise and weakness

. Typical for meningitis is the presence of meningeal symptoms, indicating irritation of the meninges. The meningeal symptom complex includes, in addition to headache, stiff neck, Kernig and Brudzinski symptoms, photophobia, and hyperesthesia of the skin. In young children, bulging and tension of the fontanel, tympanitis when tapping the skull, and a symptom of “suspension” (Lessage) are observed.

For some types of pathogens, a blurred clinical picture is observed with low-grade fever and moderate headache, absence of vomiting, meningeal monosymptoms or reduced symptoms.

General cerebral symptoms

in the form of impaired consciousness, convulsions and

signs of focal damage

to the nervous system

during meningitis are absent,

and their presence indicates encephalitis, but some authors admit their short-term presence at the onset of the disease as a manifestation of cerebral edema.

The main criterion for meningitis is an increase in the number of cells in the CSF. In viral meningitis, a lymphocytic composition of the CSF is observed.

Cytosis is represented by a two to three-digit number, usually no more than 1000 in 1 μl. The percentage of lymphocytes is 60–70% of the total number of cells in the cerebrospinal fluid. Protein and sugar levels are within normal limits. In the presence of meningeal signs, but in the absence of inflammatory changes in the cerebrospinal fluid, they speak of meningism. In some meningitis, signs of a general viral infection are observed (Table 1).

The duration of viral meningitis is 2–3 weeks. In 70% of cases the disease ends in recovery

[6], but in 10% the course is longer and may be accompanied by complications.

Features depending on the pathogen

Although in most cases of viral meningitis there is no clear clinical correlation with a specific pathogen, some features may be observed. So, often Coxsackie viruses of group B

cause diseases that occur with severe

myalgic syndrome

(the so-called epidemic pleurodynia or Bornholm's disease);

Diarrhea may occur. Both groups of Coxsackieviruses can cause pericarditis and myocarditis

.

Adenoviral meningitis

accompanied by an inflammatory reaction from the upper respiratory tract,

conjunctivitis and keratoconjunctivitis

.

Parotitis

often occurs

with damage to the parotid glands

, abdominal pain and increased levels of amylase and diastase (pancreatitis), orchitis and oophoritis. At the onset of the disease, the composition of the CSF may be neutrophilic with low sugar levels. Often the disease becomes protracted with a delay in the sanitation of the cerebrospinal fluid.

Lymphocytic choriomeningitis can also have a protracted course.

, and meningitis caused by

herpes simplex virus type 2

. With these types of disease, at the onset of the disease, the sugar level in the CSF may be below normal, which forces them to be differentiated from tuberculous meningitis.

Herpetic meningitis

often observed against the background of a primary genital infection - in 36% of women and 13% of men. In most patients, herpetic rashes precede the signs of meningitis an average of a week. Herpetic meningitis can cause complications in the form of sensory disturbances, radicular pain, etc. Relapses of the disease are described in 18–30% of cases [7].

Meningitis with herpes zoster

in some cases it occurs with minimal meningeal syndrome or asymptomatically. As a rule, it is not a monosyndromic lesion of the nervous system, but develops against the background of concomitant radicular phenomena, sensory disturbances, etc.

Meningitis with tick-borne encephalitis

observed in almost half of the sick. The onset is acute, accompanied by high fever, intoxication, pain in muscles and joints. Characterized by hyperemia of the face and upper body, severe headache, and repeated vomiting. In 20–40% of cases, a two-wave fever with a period of apyrexia of 2–6 days is observed. In the cerebrospinal fluid in the first days of the disease, neutrophilic leukocytes may predominate, the preponderance of which may persist for several days. Inflammatory changes in the CSF last a relatively long time - from 3 weeks to several months, accompanied by poor health. At the same time, diffuse neurological symptoms may be observed. Asthenic syndrome after illness, characteristic of tick-borne encephalitis, is observed in approximately 40% of those who have recovered from the disease and lasts from 1–3 months to 1 year. In 2–6%, a transition to a progressive form of the disease may subsequently occur.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of viral meningitis is difficult, especially in cases of sporadic disease. For some viral meningitis, a history or associated organ involvement may be helpful (Table 1). But the main attention is paid to laboratory diagnostics: isolating the virus from the CSF and determining the 4-fold increase in specific antibodies in the dynamics of the disease

.

Currently, large treatment centers use polymerase chain reaction

(PCR), which has high sensitivity and specificity.

Treatment of the vast majority of viral meningitis is symptomatic

.

In the acute period detoxification therapy

: solutions of glucose, Ringer, dextrans, polyvinyl lyrrolidone, etc. Moderate dehydration is used: acetazolamide, furosemide). Symptomatic drugs (analgesics, vitamins A, C, E, group B, antiplatelet agents, etc.).

For meningitis caused by herpes simplex virus type 2, intravenous acyclovir

10–15 mg per 1 kg per day for 10 days, based on 3-fold administration.

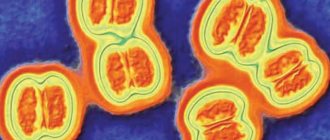

Bacterial meningitis

The causative agents can be meningococci, pneumococci, Haemophilus influenzae, staphylococci, salmonella, listeria, tubercle bacilli, spirochetes, etc. The inflammatory process that develops in the meninges is usually purulent. In recent years, the etiological structure of purulent bacterial meningitis (PBM) has changed significantly. In adults, in more than 30% of cases, the causative agent is Streptococcus pneumoniae, in people over 50 years old - S.pneumoniae and gram-negative bacteria of the intestinal group (E.coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, etc.), in children under 5 years of age in more than 30% of GBM is caused by Haemophilus influenzae type B [2, 8]. However, according to the forecast of epidemiologists, another increase in the incidence of meningococcal infection is expected in a few years.

Clinically, GBM is characterized by a more acute onset of the disease, more severe intoxication and high fever, compared to viral meningitis, and a more severe course

. CSF in GBM is turbid, with high neutrophilic pleocytosis, increased protein content; sugar levels are reduced.

Meningococcal meningitis

Meningococcal meningitis occurs mainly in children and young people. In almost half of the patients it is preceded by nasopharyngitis, which is often mistakenly diagnosed as ARVI. Against this background or in the midst of complete health, meningitis begins acutely - with chills, an increase in body temperature to 39–39.50 C, and a headache, the intensity of which increases with every hour. On the very first day, vomiting, photophobia, hyperacusis, skin hyperesthesia, and meningeal symptoms appear. There is a revival or suppression of tendon reflexes and their asymmetry. A little later, signs of increasing cerebral edema may appear: attacks of psychomotor agitation, followed by drowsiness, then coma. Focal symptoms are also possible: diplopia, ptosis, anisokaria, strabismus, etc. When often combined with meningococcemia, a characteristic hemorrhagic rash appears on the skin, the appearance of which usually precedes the symptoms of meningitis.

Possible atypical forms

, especially in patients receiving antibacterial drugs. The course of meningitis in these cases is subacute, the body temperature is subfebrile or normal, the headache is moderate, there is no vomiting, meningeal symptoms appear late and are mild, but encephalitis, ventriculitis subsequently develops and death can occur.

In infants

The onset of meningitis, including meningococcal, is manifested by general anxiety, crying, screaming, refusal to suck, sudden agitation from the slightest touch, and convulsions.

In the first hours of meningitis, the CSF is either not changed at all, or the inflammatory changes are mild. From the end of the 1st day, the CSF becomes typical for purulent meningitis. Microscopy of smears of cerebrospinal fluid sediment in most cases reveals gram-negative diplococci, mainly intracellularly. Timely initiation of adequate therapy ensures recovery in most cases.

; in the absence of this, mortality reaches 50%.

Pneumococcal meningitis

Pneumococcal meningitis can be either primary or secondary (in this case it is preceded by otitis media or mastoiditis, pneumonia, sinusitis, traumatic brain injury, cerebrospinal fluid fistulas, etc.). It often occurs in persons with a burdened premorbid background: alcoholism, diabetes mellitus, splenectomy, hypogammaglobulinemia, etc.

The onset can be either rapid (25%) or gradual, over 2–7 days. Meningeal symptoms are detected later than with meningococcal meningitis, and in very severe cases they are completely absent. Most patients experience convulsions and impaired consciousness already in the first days of the disease. The clinical course is characterized by exceptional severity due to the involvement of brain matter in the pathological process. The encephalitis that develops as a result is manifested by focal symptoms in the form of paresis and paralysis of the limbs, ptosis, oculomotor disorders, etc. In cases where meningitis is one of the manifestations of pneumococcal sepsis, a petechial rash is observed on the skin, similar to that of meningococcemia.

The CSF is very turbid, greenish, the number of cells ranges from 100 to 10,000 or more in 1 μl, and cases with low cytosis are especially severe. The protein level increases to 3–6 g/l and higher, the sugar content decreases. When smear microscopy, gram-positive diplococci located extracellularly can be detected.

The prognosis for pneumococcal meningitis is worse than for meningococcal meningitis: even with early therapy, due to the rapid consolidation of pus, the process progresses and mortality reaches 15–25%.

Meningitis caused by Haemophilus influenzae type B

Meningitis caused by Haemophilus influenzae type B most often affects children under 1.5 years of age,

but it can also occur in older children, in adults after 65 years of age, and sometimes in young and middle-aged people. According to some data [9], in recent years, up to 95% of all cases of GBM are caused by pneumococcus and Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib).

The symptoms of Hib meningitis depend on the age of the patient and the duration of the disease. The onset can be sudden, with a sharp increase in body temperature to 39–400 C, repeated vomiting, and severe headache. After a few hours, convulsions, impaired consciousness, coma occur, and death may occur. A gradual development of the disease is also possible, with symptoms associated with the primary focus of Hib infection first appearing (epiglottitis, cellulitis, purulent otitis, arthritis, etc.), and then meningeal, cerebral and focal symptoms are added. The CSF is cloudy and green in color. There is a characteristic discrepancy between turbidity of the cerebrospinal fluid (it is caused by a high concentration of the pathogen in the CSF) and relatively low cytosis. Meningitis can occur sluggishly, in waves, with alternating periods of improvement and deterioration. Untimely and/or inadequate antibiotic therapy leads to death, the frequency of which reaches 33% [5].

Purulent meningitis of other etiologies (staphylo- and streptococcal, klebsiella, salmonella, caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, etc.) are usually secondary (oto- and rhinogenic, septic, after neurosurgical operations) and are relatively rare.

Diagnosis

The acute onset of the disease, a combination of fever, intoxication, meningeal syndrome, and characteristic changes in the CSF (high neutrophilic pleocytosis, increased protein content and decreased glucose levels) give grounds to diagnose purulent meningitis.

The etiology of GMB can be tentatively established by bacterioscopy of a CSF smear and clarified using bacteriological examination of CSF and blood. However, in patients who have already received antibiotics, the likelihood of detecting the pathogen using these methods is low. Therefore, various immunological methods are used to detect pathogen antigens and antibodies to them (VIEF, latex agglutination). The etiology of meningitis is most accurately determined using PCR [10]. Differential diagnosis for both purulent and serous meningitis is carried out between meningitis of various etiologies, as well as with other diseases accompanied by meningeal syndrome and neurological disorders: cerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhage, brain injuries, brain abscess and other volumetric processes, cerebrovasculitis, infectious diseases with meningeal syndrome, etc.

Treatment

For GBM, unlike viral ones, antibacterial therapy

which is urgent.

At the first stage, before the etiology of

GBM is established, one of the following antibiotics is recommended: ampicillin/oxacillin (200–300 mg/kg per day); ceftriaxone (100 mg/kg/day) or cefotaxime (150–200 mgkg); in young children, a combination of ampicillin with ceftriaxone [2, 11]. In the future, antibacterial therapy is adjusted depending on the etiology of meningitis and the sensitivity of the pathogen. Antimicrobial drugs must be prescribed in maximum doses that provide bactericidal concentrations in the CSF [12]. In patients with secondary GBM, sanitation of the primary lesion is necessary.

Tuberculous meningitis

Tuberculous meningitis most often affects children and the elderly

. The disease in most cases is secondary in nature, spreading from primary foci in the internal organs (lungs, lymph nodes, kidneys). It is also possible to damage the membranes from subependymal caseous foci that existed for a long time without manifestations. Provoking factors are immunodeficiency states, alcoholism, exhaustion, drug addiction.

In the membranes of the base of the brain, dense infiltrates form with compression of the cranial nerves and vessels of the circle of Willis. The disease develops gradually, weakness, adynamia, sweating, increased fatigue, and emotional lability appear. A headache occurs, increasing in intensity, low-grade fever, and vomiting. Damage to the oculomotor nerves appears early.

In the CSF – lymphocytic pleocytosis, protein-cell dissociation, hypoglycorrhachia. The diagnosis is based on the determination of antigen and antibodies to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the CSF using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and the use of PCR.

The treatment uses isoniazid (5 mg/kg/day) in combination with rifampicin (10 mg/kg/day) and pyrazinamide (15–30 mg/kg/day). Duration of treatment is 9–12 months.

Meningitis with syphilis

Meningitis in syphilis is observed in all stages of clinical manifestations of the disease and in asymptomatic cases. It may have a manifest or blurred clinical picture. From 10 to 70% of people with early syphilis have lymphocytic pleocytosis in the CSF, which is often combined with an increase in protein. In diagnosis, taking into account the polymorphic clinical picture, the main role is given to laboratory tests: a complex of serological reactions with cardiolipin and treponemal antigens in serum and CSF; microhemagglutination reactions of Treponema pallidum [13]. Treatment is carried out with penicillin (2–4 million units intravenously every 4 hours) or 2.4 million units/day intramuscularly with probenecid (500 mg orally 4 times/day). The course of treatment is 10–14 days.

Meningitis due to Lyme borreliosis

Meningitis in Lyme borreliosis is a common complication of the disease. It may occur in combination with erythema migrans

– a characteristic marker of the disease.

The disease is usually preceded by ticks biting when visiting the forest. The course of meningitis is polymorphic, meningeal signs can be moderately expressed. In the CSF there is lymphocytic pleocytosis. Serological tests play a decisive role in the diagnosis: immunofluorescence reaction or ELISA with the B.burgdorferi

. Treatment is carried out with intravenous penicillin 24 million units/day for 14–21 days or ceftriaxone 1 g 2 times a day.

Specific prevention

Specific prevention of bacterial meningitis. Currently, there are vaccines to prevent meningococcal meningitis, Haemophilus influenzae and pneumococcal infections. Vaccination is carried out in high-risk groups, as well as for epidemiological reasons.

The list of references can be found on the website https://www.rmj.ru

References

1. Menkes JH Textbook of Child neurology, 4ed. Lea & Feiberg, London. 1990; 16–8.

2. Roos KL Meningitis. 100 maxims in neurology. Arnold, London, 1996.

3. Pokrovsky V.I., Favorova L.A., Kostyukova N.N. Meningococcal infection. M., Medicine, 1976.

4. Lobzin V.S. Meningitis and arachnoiditis. L., Medicine, 1983.

5. Acute neuroinfections in children. Ed. A.P. Zinchenko. L., Medicine, 1986.

6. Sagar S., McGir D. Infectious diseases. Neurology. Ed. M. Samuels. M., 1997; 193–275.

7. Dekonenko E.P., Lobov M.A., Idrisova Zh.R. Damages of the nervous system caused by herpes viruses. Neurological Journal. 1999; 4:46–52.

8. Demina A.A. Epidemiological surveillance of meningococcal infection and purulent bacterial meningitis. Epidemiology and Infectious Diseases 1999; 2: pp.25–8.

9. Sorokina M.N., Skrinchenko N.V., Ivanova K.B. and others. Meningitis caused by Haemophilus influenzae type B: diagnosis, clinical picture and treatment. Epidemiology and infectious diseases. 1998; 6:37–40.

10. Platonov A.E., Shipulin G.A., Koroleva I.S., Shipulina O.Yu. Prospects for diagnosing bacterial meningitis. Journal of Microbiology. 1999; 2; 71–6.

11. Guidelines for the clinic, diagnosis and treatment of meningococcal infection. Appendix to the order of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, 1998.

12. Padeyskaya E.N. Antimicrobial drugs for the treatment of purulent bacterial meningitis. RMJ, 1998; 6 (22): 1416–26.

13. Marra CM Neurosyphilis. Current Therapy in Neurologic Disease, ed. R. T. Johnson, J. W. Griffin. Mosby, 1997; 136–40.

| Applications to the article |

Lumbar puncture

Lumbar puncture is rightfully considered the most effective method for diagnosing the disease. Cerebrospinal fluid examination reveals mildly elevated protein levels, normal glucose concentrations, and lymphocytosis.

In the first two days after infection of the body, cytosis is predominantly neutral. That is why it is worth repeating the study after 8-12 hours to monitor whether a lymphocytic shift has appeared or not. As a rule, the glucose concentration in viral meningitis is normal. Its decrease indicates tuberculous or fungal meningitis, as well as a non-infectious disease.

Examination of the cerebrospinal fluid also suggests isolation of the virus from it. However, this method is rather auxiliary, since it does not allow obtaining an extensive clinical picture of the disease. This is due to the fact that the virus is present in the cerebrospinal fluid in small quantities. Moreover, the disease can be caused by a variety of viruses, and they need to be cultured differently. To isolate the virus, you need to obtain at least two milliliters of cerebrospinal fluid, and then immediately send the material to the laboratory.

The virus can be isolated not only from cerebrospinal fluid, but also from other sources. For example, adenoviruses and enteroviruses can be detected in a patient’s stool, cytomegalovirus in urine, enteroviruses and arboviruses in blood, and mumps virus and enteroviruses in nasopharyngeal washings. However, it must be taken into account that the presence of enteroviruses in stool may not indicate viral meningitis, but a recent infectious disease.

Meningococcal infection, routes of infection

Meningococcal infection is transmitted by airborne droplets. The source of infection is always a person suffering from acute nasopharyngitis, with an acute generalized form of meningococcal infection, or a healthy carrier. Usually the number of carriers of meningococcus is no more than 5 percent, but during an epidemic in the source of infection the proportion of carriers can reach 50%. In this case, carriage of meningococcus is usually short-lived, about a week.

Periodic rises in the disease occur approximately every 10 to 12 years.

When should you see a doctor?

You should seek medical help as soon as possible if you notice the following symptoms (all or some of them) in yourself or someone in your family:

- heat;

- excruciating headache;

- confusion;

- vomit;

- stiff neck muscles;

- rash.

Do you have meningeal symptoms? Call an ambulance immediately!

Checking for meningeal symptoms can help make a preliminary diagnosis. It can be done at home.

Symptom of neck stiffness

The patient lies on his back, without a headboard. While holding his chest with one hand, the other should be placed under the occipital region and try to bring the chin closer to the sternum. If the symptom is positive, then due to the increased tone of the muscles of the back of the head, it will be impossible to do this; the movement will cause involuntary resistance and pain in the patient. A measure of the severity of muscle tension is the distance between the patient's chin and sternum.

Kernig's sign

The patient lies on his back. You should bend one leg at the hip joint at an angle of 90°, and then try to straighten it at the knee joint (Fig. 4). If the symptom is positive, then straightening the leg at the knee will be impossible, this will cause resistance and pain.

Kernig's sign. Source: Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology/Open-i (Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported)

Brudzinski's sign

This set of signs of meningitis includes several symptoms:

a) upper - bringing the chin closer to the chest while examining the rigidity of the muscles of the back of the head causes involuntary bending of the legs at the knees and bringing them in the stomach;

b) medium - the same reaction of bending the legs will be caused by pressing on the stomach above the pubic bones;

c) lower - examined simultaneously with Kernig's symptom - when trying to straighten one leg at the knee joint, the second leg bends at the knee and is brought to the stomach.

Lower and upper Budzinski's symptoms. Source: Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology/Open-i (Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported)

Lesage's sign

In children of the first year of life and newborns, due to the natural increased tone of the limbs, the above tests are not informative. They are tested for Lesage's symptom: the child, raised by the armpits, pulls the legs towards the stomach and keeps them in a taut position (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Lesage's sign. Source: image from the PSPbSMU website

You can learn more about the technique for checking meningeal symptoms by watching Video 1.

Video 1. Technique for checking meningeal symptoms. Source: ONMedU

Bacterial meningitis is a serious disease that can be fatal within a few days without prompt antibiotic treatment. Also, starting treatment late increases the risk of permanent brain damage. Therefore, even if you are not sure of your assumptions, feel free to consult a doctor. It is also important to consult a specialist if a family member or someone you live or work with has meningitis. You may need to take medicine to prevent infection.

At-risk groups

There are factors that increase your risk of getting meningitis. These include:

- Age. Newborns, children of primary school age, adolescents 13-17 years old, as well as older people are considered more susceptible to meningitis pathogens.

- Organized teams. Outbreaks of meningococcal infection have been observed more than once in places where a large number of people are forced to stay in one area for a long time: in barracks, university campuses, etc.

- Medical factors. This may include certain health problems: immunodeficiency conditions and diseases of the immune system, HIV infection, absence of a spleen, taking certain groups of medications that lower natural immunity (chemotherapy, cytostatics, etc.), as well as surgical interventions.

- Contact with infections that cause meningitis. This factor is especially relevant for microbiologists, who may regularly come into contact with meningitis pathogens due to the specific nature of their work.

- Trips. Visiting geographic areas where a particular pathogen is endemic (its characteristic habitat) also increases the risk of meningitis. For example, staying in the countries of the meningitis belt in Africa.

What is this?

Meningitis (from the Latin meninx - “brain membrane”, suffix -itis - “inflammation”) is an inflammation of the membranes of the brain and spinal cord.

It is the membranes, and not the brain tissue itself. Inflammation of the brain is encephalitis (from the Latin encephalon - “brain”, suffix -itis - “inflammation”).

The brain has three membranes:

- hard;

- arachnoid (arachnoid);

- soft (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Meninges of the brain.

Source: SVG by Mysid, original by SEER Development Team [1], Jmarchn / Wikipedia (Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license) The dura mater is adjacent to the inner surface of the skull. It consists of two leaves: outer and inner. The outer leaf is tightly adjacent to the inner surfaces of the bones of the vault and base of the skull, the inner leaf forms dense outgrowths of this shell into the cranial cavity, which play the role of a frame for the brain and divide it into several sections. Between the leaves there are important formations - venous sinuses. They collect blood, which flows from the brain, enters the jugular veins and then into the heart through the superior vena cava.

The arachnoid membrane is thin, it occupies an intermediate position between hard and soft and connects them to each other.

Finally, the pia mater is loose and covers the brain, extending into all its grooves and crevices. In the thickness of the soft shell there are a large number of vessels that nourish the brain tissue.

Most often (perhaps due to the abundant blood supply), it is the pia mater that becomes inflamed. However, inflammation of the dura and arachnoid membranes also occurs. If both the arachnoid and soft membranes are inflamed at the same time, the disease is called leptomeningitis, if we are talking only about the hard membrane - pachymeningitis.

The spinal cord also has dura, arachnoid and pia mater. In structure, they are almost no different from the membranes of the brain. Their inflammation is also called meningitis. It is dangerous because it can spread to the tissue of the spinal cord itself. However, these will be different pathological conditions with their own complications.

Serodiagnosis

The diagnosis can also be made based on the results of serodiagnosis. However, in most cases, such a study is carried out only to clarify the disease, and not to diagnose it. Using PCR (polymerase chain reaction), DNA of the herpes simplex virus can be detected in the cerebrospinal fluid.

In addition to specific studies, the patient must also undergo a number of general studies:

- general blood analysis;

- determination of ESR;

- hematocrit;

- plasma glucose;

- KFK;

- creatinine.

Usually, when diagnosing viral meningitis, you can do without instrumental studies such as EMG, CT, MRI, EEG. Research is carried out exclusively in case of a questionable or atypical diagnosis.

Sources

- Global, regional, and national burden of meningitis, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016 [Electronic resource] // The Lancet. Neurology, 2021.

- Epidemiology of Meningitis Caused by Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenza [Electronic resource] // cdc.gov, 2021.

- Rebecca M. Cantu; Joe M Das. Viral Meningitis [Electronic resource] // NCBI, 2021.

- Meningitis [Electronic resource] // who.int

- What Do You Want to Know About Meningitis? [Electronic resource] // healthline.com, 2021.

- YouTube. Research and assessment of meningeal symptoms in a child.

- Clinical protocol for diagnosis and treatment. Meningitis in children and adults [Electronic resource] // rcrz.kz, 2021.

- Kenadeed Hersi; Francisco J. Gonzalez; Noah P. Kondamudi. Meningitis [Electronic resource] // NCBI, 2021.