Intellectual disabilities in children

The clinical picture of intellectual impairment is varied. Symptoms should be considered in accordance with the classification: with quantitative changes, there is a decrease in learning ability, difficulties/impossibility of self-care, with qualitative changes, a decrease in intelligence is combined with mosaic, partial development of individual functions.

Impaired mental function.

The level of intelligence is below average, reaching levels borderline with mental retardation. There are two variants of the clinical picture. If cognitive activity is impaired due to insufficient development of the emotional-volitional sphere, a lack of interest in cognitive activity comes to the fore: children are active, impulsive, and prefer simple games. They are not interested in creative and educational activities; they are difficult to organize and encourage reading and drawing. The second option is insufficient formation of the prerequisites for intelligence (memory, performance, attention). Children lack initiative, are not independent, are overly active or passive, get tired quickly, work at a slow pace (signs of cerebrovascular disease).

Moronism.

It is characterized by the primitiveness of thinking, its attachment to specific, visual situations, insufficient differentiation of emotions, and weakness of volitional impulses. Patients later master self-care skills, are able to dress independently, and perform hygiene procedures. According to a special curriculum, they master writing, reading, and counting. Teenagers learn simple working professions.

Imbecility.

Thinking is slow, stiff, experience is difficult to adopt. Intellectual-mnestic functions are reduced. Social interaction is limited and learning skills are impossible. Children are delayed in mastering self-care and simple homework.

Idiocy.

Characterized by a lack of speech and the ability to establish productive contact with others (with the exception of single executions of simple commands). There are often concomitant neurological pathologies and diseases of internal organs. Mobility is limited and self-care is not available.

Damaged and deficient development.

The unevenness of intellectual impairments is explained by the mosaic nature of the damage to the central nervous system: some functions are developed and continue to develop at a normal pace, others slow down (depending on the location of the damage - speech, spatial, auditory-verbal perception, memorization). Complex hierarchical connections fall apart, and intellectual retardation develops. Deficient development leads to intellectual impairment based on a primary defect - pathology of the analyzer (hearing, vision), motor system.

Distorted and disharmonious development

. It is caused by an ongoing pathological process that disrupts the uniform development of functions. Children have well-developed verbal intellectual functions, but adaptation is complicated by the difficulty of assimilation and understanding of social rules. Or the child has unique mathematical abilities, but everyday skills are difficult.

Causes of mental retardation

- hereditary factors, including pathology of the generative cells of the parents (this group of oligophrenia includes Down's disease, true microcephaly, enzymopathic forms);

- intrauterine damage to the embryo and fetus (hormonal disorders, rubella and other viral infections, congenital syphilis, toxoplasmosis);

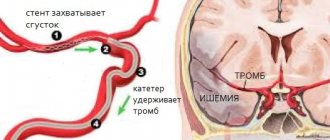

- harmful factors of the perinatal period and the first 3 years of life (asphyxia of the fetus and newborn, birth trauma, immunological incompatibility of the blood of mother and fetus - conflict over the Rh factor, head injuries in early childhood, childhood infections, congenital hydrocephalus).

Intelligence and thinking

The characteristic of intelligence is also given by its most important component - thinking. According to one of the classifications there are:

- Visual-effective thinking is the simplest. It is formed in the first years of life, when the child looks at adults and repeats their actions to get dressed, use a spoon to eat, etc. ;

- Concrete-figurative thinking . When a child tries to draw conclusions about things that he does not observe, but only imagines or remembers, he masters concrete figurative thinking;

- Abstract thinking . The highest level of development of thinking is abstract thinking, which is used for learning in high school. Abstract thinking requires the ability to work with concepts such as mathematical operations, physical laws and philosophical categories.

Treatment methods

After diagnosing the condition, depending on the indications, the specialist can prescribe drug therapy, but the most important thing is that he connects the child to a system of psychological and pedagogical assistance, which includes correctional classes, in most cases, with three specialists. This is a defectologist, speech therapist and psychologist. Very often one teacher has two specializations, for example, a speech therapist-defectologist. Help from these specialists can be obtained at correctional centers or within a preschool educational institution. In the latter case, the child, accompanied by his parents, must undergo a psychological, medical and pedagogical commission. Early identification and timely connection of a child to psychological and pedagogical correction directly affect the further prognosis and level of compensation for identified developmental disorders. The sooner it is identified and connected, the better the result!

When composing stories based on individual and serial plot pictures, the majority of subjects in the clinical group were unable to cope with the task without errors and made significantly more of them than healthy subjects. Thus, 43% of patients with depression had clear difficulties in assessing the emotional and expressive elements of situations depicted in pictures, humor (normally, such difficulties were encountered only in 14% of subjects), 64% showed inattention to the subtle details and nuances of the image (normally there were no such cases). Patients with depression, in cases of difficulties, were less likely than mentally healthy subjects to independently optimize their activities or correct initially put forward erroneous hypotheses, relying on leading questions and instructions from a psychologist. It should also be noted that subjects in the control group more often showed their own activity in searching for perceptual and semantic supports for successfully completing tasks; they less often required outside help.

The results of serial mental counting (subtracting “from 100 to 7”) showed that patients with depression required more time to complete the task: while subjects in the control group spent an average of 1 minute. 10 seconds, then patients with depression – 1 minute. 51 sec. They also made more mistakes. It is significant that while in the control group errors were more common at the initial stages of the task, patients with depression made errors at all stages of counting with approximately the same frequency. This task generally turned out to be not very simple for all subjects. This is evidenced by the fact that even the subjects of the control group in a number of cases needed confirmation of the correctness of their own actions (this need, as a rule, was realized in the form of a questioning clarification of the instruction “So, are we subtracting 7?”).

But in the clinical group, it was not clarifications that were more often recorded, but rather the loss of instructions; additional repetition was required to continue the activity. In general, we can say that the performance of the task by subjects in the control group was more automated and internalized in nature, while patients with depression more often used “external” verbal methods of mediation, i.e. they recited aloud the counting operations being performed (such persistent recitation was found in 21% of healthy subjects and in 64% of patients with depression). It also seems important that the inclusion of counting operations in the plan of external speech, as a rule, did not contribute to the improvement of activity; the patients still made mistakes again. In the control group, verbal mediation practically eliminated the occurrence of new errors and significantly improved performance.

The data obtained allow us to make a number of assumptions about some psychological features of the functioning of the mediation of mental activity during normal and pathological aging. The arsenal of mediation methods that is formed throughout ontogenesis (determined by the action of a complex of environmental and biological factors, which is at the same time common to all people of a given culture and at the same time has individual characteristics) has a complex multi-level structure. During normal aging, when mental processes proceed more or less optimally, many methods of self-regulation and mediation are so automated and internalized that reflection is not always available (this is evidenced by the self-reports of the subjects).

Mentally healthy elderly people resort to additional mediating techniques mainly in cases where the volume of memorized material is large or the nature of the activity requires increased attention and a significant load on the working memory, and these techniques in most cases significantly improve task performance. As for affective disorders, the results of the study show that in the majority of patients examined, the qualitative and speed indicators of mnestic and intellectual activity change. There are distinct difficulties in engaging in tasks, fluctuations in attention and level of achievement, exhaustion, and increased inhibition of memory traces. These facts are consistent with modern clinical data that with depression during aging, concentration of attention is impaired, there are difficulties in making decisions, and clear mnestic-intellectual changes are recorded in 5-25% of patients (Kontsevoy, 1999). The changes also affect the methods of self-regulation and mediation: their range narrows, they often lose their internalized character, become ineffective, and are less able to compensate for difficulties in mnestic-intellectual tasks. Such negative manifestations, apparently, can be caused both by the state of brain structures and by emotional and motivational disorders.

Consideration of the processes of self-regulation and mediation of mental activity in depression seems promising for understanding the mechanisms of functioning of the complex of affective and mnestic-intellectual changes characteristic of this nosology.

mediation of activity – previous | next – Alzheimer's type dementia

A. R. Luria and psychology of the 21st century. Content

Components of Intelligence

The components of intelligence are divided into hereditary and acquired. The hereditary components of intelligence include ability, giftedness and determination. Acquired components of intelligence include upbringing, education and life experience. The ratio of innate and acquired components of intelligence is unique for each individual.

If I ever write about medical psychology, I will definitely define these concepts and talk a little about each. And for now we are moving on.