Epilepsy is not only “one of the most common and severe, but at the same time potentially treatable and socially significant diseases of the brain” [1], but also reflects a broad interdisciplinary problem in which the interests of neurologists, pediatricians, psychiatrists, neurosurgeons, etc. intersect. Prevalence Epilepsy in industrialized countries is 40-70 patients per 100,000 population per year [2], and in developing countries - 35-190 per 100,000 [3]. In the general population of our country, this figure is 3.39 per 1000 population [4]. Despite the obvious successes in the treatment of epilepsy, as well as the emergence of new effective anticonvulsants, the problem of resistance remains key in epileptology. Moreover, more than 30-40% of patients with epilepsy do not achieve complete control of seizures [5, 6]. WHO estimates that 15 out of 50 million people with epilepsy continue to have seizures despite treatment with anticonvulsants [7]. Approximately 30% of patients with focal epilepsy develop drug resistance during their lifetime, in which the chance of achieving complete seizure control with continued drug therapy is no more than 8% [8].

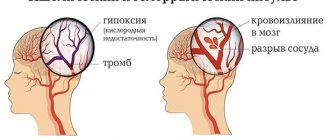

Generally accepted criteria for pharmacoresistance were proposed by A. Berg [9]: 1) persistence of seizures when using 2 anticonvulsants; 2) 1 attack per month during 18 months of observation; 3) attack-free period of no more than 3 months during 1.5 years of observation. Pharmacoresistance, as one of the most serious problems in the treatment of epilepsy, leads to many severe complications, including trauma, damage to a number of organs and systems, an increased risk of death and severe psychological and psychiatric consequences. Such patients are significantly more likely to experience concomitant cognitive and mental disorders [10], and they are 1.5–2 times more likely to suffer traumatic brain injuries, burns, dental damage, etc. [11]. Their mortality rate is higher compared to curable patients [8], especially in cases of nocturnal and generalized seizures, in which the risk of sudden death increases 40 times [12–15].

There are many works devoted to mental disorders in drug-resistant epilepsy [16-20], which address the issues of differential diagnosis of true resistance and pseudo-resistance [21, 22], the close association of drug resistance with an increased risk of psychotic [23], affective [19, 24- 26], anxiety [24], cognitive [27–29] and other disorders that, together with uncontrolled seizures, significantly reduce the quality of life of patients [30–34]. Moreover, not only drug resistance is a risk factor for mental disorders, but mental disorders themselves significantly increase the risk of developing drug resistance [20] by increasing the severity of brain dysfunction [35].

Methods to overcome resistance can be both medicinal and non-medicinal [36]. There is evidence in the literature of a decrease in the frequency of attacks when veramapil [37] and statins [38] are added to basic anticonvulsant therapy. More and more information is accumulating about the anticonvulsant properties of phytocannabinoids [39]. Non-medicinal methods include various diets (ketogenic diet, modified Atkins diet), which, according to A. Sharma et al. [36] also help reduce the frequency of attacks or achieve remission. There is scattered data on the effectiveness of acupuncture, psychotherapy, and, in particular, biofeedback, autogenic training, as well as deep and progressive relaxation [40].

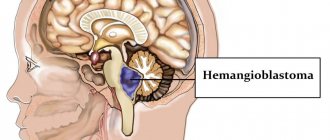

Non-drug methods of overcoming pharmacoresistance also include surgical treatment, the indications for which are: attacks that have a focal onset, limiting daily life and reducing the quality of life; establishing criteria for pharmacoresistance or the presence of significant side effects from taking anticonvulsants [41]. Currently, the main types of surgical treatment are: resection interventions (removal of the pathological focus - arteriovenous malformations, cavernous malformations, brain tumors, selective amygdalohippocampectomy, cortical resection, partial lobectomy, lobectomy, hemispherectomy), palliative interventions (callosotomy, multiple subpial incisions), alternative methods (vagus nerve stimulation, deep brain stimulation, stereotactic destruction, ablations) [42]. More than ½ of all surgical procedures for drug-resistant epilepsy involve the anterior medial lobectomy method for temporal lobe epilepsy [43], aimed at removing the epileptogenic zone, which includes both the “onset” zone of the attack and potentially possible epileptogenic areas.

Historical aspects of surgical treatment of epilepsy: control of mental disorders

Surgical methods of treating epilepsy have long remained the subject of empirical research by separate groups of enthusiastic scientists in different countries of the world. However, their activities played a decisive role in the further history of the development of this new direction of therapy. These studies at that time did not have a strict scientific methodology, technique and technology. However, even then, scientists were concerned about the most pressing problems that arise when assessing the results of surgical intervention, such as seizure control, the level of social adaptation, cognitive impairment and mental disorders.

The history of surgical treatment of epilepsy dates back to ancient times, when Greek and Roman doctors performed craniotomy to relieve epileptic seizures that developed after traumatic brain injury (TBI) [44]. There are separate references to this method of surgical intervention in the works of authors of the Middle Ages [45] and the Renaissance [44]. Only in 1828, the American surgeon B. Dudley [46] first published a description of a series of clinical cases on the effectiveness of trepanation for the treatment of epilepsy, and in 1886 V. Horsley performed the first brain surgery on a patient with post-traumatic epilepsy, which resulted in complete reduction of seizures [47]. In our country, surgical treatment of epilepsy was first described in 1895 by V.M. Bekhterev [48]. During the same period, V.I. Razumovsky (1893), and subsequently G.F. Zeidler (1896) successfully used the Horsley operation (surgical extirpation of the cerebral cortex) in patients with Jacksonian epilepsy [49].

The introduction of electroencephalography (EEG) methods into practice contributed to the further development of surgical treatment of epilepsy. Thus, in the 30s of the 20th century, groups of researchers led by W. Penfield and H. Jasper identified the essential role of neurophysiological research in epilepsy surgery and the need for resection of mesiotemporal structures to achieve seizure control [47, 50]. The results of the first temporal lobectomies were published by W. Penfield and H. Flanigin [51] in 1950. The selection of patients for surgery was based on the clinical picture of attacks, the absence of “severe” mental disorders, as well as EEG data, pneumographic and radiological studies. The effectiveness of surgical intervention was quite high: complete control of attacks was observed in 53% of patients, a reduction in the frequency of attacks by more than 50% was observed in 25% of patients. However, the authors did not identify significant changes in the behavior and cognitive functioning of patients. In the USSR, temporal lobectomies were first performed by A.G. Zemskoy (1960), Yu.N. Savchenko (1962) and Yu.I. Belyaev (1963) [49].

Since the middle of the 20th century, more and more works began to appear in foreign literature on the effect of surgical treatment of epilepsy on mental disorders. Thus, according to a study conducted in 1951 by P. Bailey [52], out of 25 operated patients, 4 showed an improvement in their mental state (“they became calmer, more serene and pliable”), while in 3 the condition worsened ( “became more talkative and hyperactive”), 2 of them required hospitalization in a psychiatric hospital. The results of another study [53] conducted during the same period showed that after temporal lobectomy, patients showed impaired auditory-verbal memory, a decrease in the level of aggressiveness, “switching aggression to depression with and without hypochondriacal experiences,” as well as improved interpersonal contacts and changes in sexual sphere (usually in the form of increased libido). In their study, English neurosurgeons M. Falconer and E. Serafetinides [54], assessing the effect of surgery on comorbid mental disorders, revealed a decrease in the number of attacks, accompanied by an improvement in the mental state of patients. In 1972, D. Taylor [55] published the results of a prospective (duration 2–12 years) study involving 100 patients who underwent surgical treatment of epilepsy using anterior temporal lobectomy. Efficacy in the postoperative period indicated heterogeneous postoperative dynamics of the mental state of patients and, according to the authors, was associated with results in achieving seizure control: improvement in mental state in the group of “neurotics” (mainly in relation to anxious, depressive and phobic conditions) and “ psychopaths" (mainly due to a decrease in aggressiveness), lack of dynamics, and in some cases the emergence of de novo

. During the entire observation period, 37 patients were hospitalized in a psychiatric hospital, of which 19 had psychotic disorders, and 5 had suicidal attempts.

The study of the effect of surgical treatment of epilepsy on mental disorders was also discussed in the domestic literature [16, 56]. So, Yu.V. Konovalov pointed out that after surgery in patients [16]. The results of the study by P.M. Panchenko et al. [57] showed that unilateral surgical intervention on cortical, archi- and paleocortical epileptogenic foci did not lead to an increase in “personality defect”, and the cessation or reduction in the frequency of attacks had a beneficial effect on the mental state of patients. The results published by V.M. Ugryumov [16] also indicate that after surgical treatment of epilepsy there is no “destruction of the patient’s personality”, and complete or partial achievement of seizure control contributes to an improvement in mental state. I.T. Viktorov [58], when describing the clinical variants of “mental defect” (psychoorganic, epileptic, with psychophysical infantilism, schizoepileptic and a combination of epileptoid and hysterical character traits) in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy after its surgical treatment, emphasized “the possibility of their functional reversibility, especially in the acute phases of epileptic process".

Researchers were more unanimous when assessing the effect of surgical treatment of epilepsy on cognitive functioning: most authors noted a deterioration in cognitive processes in such patients [59, 60]. Thus, in the work of B. Milner [61], patients after temporal lobectomy on the left (dominant hemisphere) showed a deterioration in verbal memory, and in those who had it on the right, a deterioration in visual memory. In 1967, C. Blakemore [62] published the results of a prospective 10-year study of 86 patients who underwent anterior temporal lobectomy. In the case of resection of the temporal lobe in the dominant hemisphere, patients experienced auditory-verbal memory impairments, which persisted for about 3 years and then quickly resolved.

The current stage of development of surgical treatment of temporal lobe epilepsy was a consequence of the introduction of neuroimaging and standardization methods into surgical practice. The study of data obtained as a result of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) made it possible to diagnose epileptogenic brain lesions, previously detected either after surgery or during autopsy of patients with long-term epilepsy [49]. Signs of hippocampal sclerosis, various heterotopias, focal cortical dysplasias [63, 64], etc. were described. An important milestone in standardizing the assessment of the effectiveness of surgical treatment of epilepsy was the inclusion in the preoperative preparation of a neuropsychological examination aimed at assessing the persistence and severity of cognitive impairment, as well as the possibility of their compensation after surgery [41, 47, 65]. In addition, standardization of the diagnostic qualification of the mental state of patients with epilepsy began to be carried out using modern psychiatric classifications (ICD-10 and DSM-IV), structured and semi-structured clinical interviews, generally accepted psychometric scales, and the results of surgical treatment of epilepsy - using the surgical treatment outcome scale [66]. The latter included 4 blocks of parameters (absence of attacks that negatively affect the quality of life; rare attacks that affect the quality of life; significant improvement; insignificant improvement or deterioration), which made it possible to compare the results of different studies.

The effect of surgical treatment on epileptic seizures (current data)

The goal of surgical treatment of epilepsy is to achieve complete remission or reduce the frequency of seizures that impair quality of life. In 2001, the first comparative randomized controlled trial (RCT) [67] of surgical and medical treatment of drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy was published, the results of which showed the benefits of surgery in assessing seizure control: within a year after temporal lobectomy with continued medical treatment in 58% Patients had no seizures, while in the control group this figure was 8%. Another RCT comparing surgery for drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy with long-term drug therapy was conducted in 2012 by J. Engel et al. [68]. In this study, after temporal lobectomy, 11 of 15 patients were seizure-free for 2 years, whereas none of the 23 patients treated with medication achieved complete remission. Despite the convincing results of these studies, indicating the superiority in the effectiveness of surgical intervention, it should be noted that there are limitations in the size of the analyzed samples, which included only patients with temporal lobe epilepsy, which does not correspond to the entire phenotypic spectrum of pharmacoresistant focal epilepsy.

D. Schmidt and K. Stavem [69] conducted a meta-analysis of 20 comparative studies involving operated and non-operated patients with drug-resistant epilepsy, 19 of which were non-randomized, and 17 included only patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. The results of the meta-analysis showed that 12% of patients in the drug therapy group and 44% of those undergoing surgery achieved complete remission. At the same time, 36% of patients in the latter group managed to completely stop antiepileptic therapy. A recent meta-analysis [70], which included 20 studies in both children and adults (18 non-randomized studies, 11 evaluated only patients with temporal lobe epilepsy, 1 studied Lennox-Gastaut syndrome), confirmed previous data: complete remission was achieved 57% of operated patients and 15.3% of patients from the control group. At the same time, in the main group there was a reduction in the dosages of anticonvulsants, and in 19.4% of cases - their complete withdrawal, while in the control group there was no reduction in dosages, and complete withdrawal of the drugs was possible in only 3.9% of patients.

The results of domestic studies, mostly uncontrolled, also indicate the effectiveness of surgical treatment of epilepsy. Thus, according to a prospective 12-month study [71], which observed 26 patients who underwent surgical treatment of epilepsy, 69% achieved complete seizure control, in 19% the outcome of the operation corresponded to Engel class 2, in 4% - 3rd, 8% - 4th. Another study [72], which included operated patients with MR-negative drug-resistant epilepsy, showed similar results: 66% of patients achieved complete seizure control. According to M.R. Mamathanova et al. [73], when performing temporal resections, the outcome of the operation corresponded to Engel class 1 in 75.4% of adult patients, and for extratemporal resections - in 58.9%.

The search for real ways to increase the effectiveness of surgical treatment of epilepsy is, first of all, aimed at establishing predictors of effectiveness. Thus, according to the results of an analysis of a recently published systematic review [74], independent factors for a favorable outcome of surgery in terms of seizure control include the presence of mesiotemporal sclerosis or tumor, concordance of MRI and EEG, indication of a history of febrile seizures, unilateral interictal epileptiform activity and completeness of resection epileptogenic zone. The authors indicate that a history of TBI, encephalomalacia or vascular malformations, as well as epileptiform activity determined after surgery did not have a significant effect on the outcome of surgical treatment of epilepsy. At the same time, the absence of changes on MRI, preoperative invasive EEG monitoring, the presence of focal cortical dysplasia and other malformations, as well as left-sided resection, although they can worsen the prognosis of surgical treatment, but, according to V. Vakharia et al. [75] are not a reason to refuse it.

The effect of surgical treatment of epilepsy on cognitive functions (current data)

The cognitive “turn” in brain science has become a powerful factor in terms of interdisciplinary research into cognitive functions in epilepsy and the impact of various treatment methods, including surgery, on them.

It is known that epilepsy is a factor that negatively affects cognitive functions. Even in adult patients, memory, speed of psychomotor reactions, and executive functions deteriorate over the course of a year of illness [76]. In patients with drug-resistant epilepsy, cognitive impairment most often affects the areas of attention and information processing, as well as visual and verbal memory [77, 78].

Despite the interest of researchers in studying the consequences of surgical intervention for epilepsy in the field of cognitive functioning, the results obtained are quite contradictory. E. Sherman et al. [79], based on a systematic review, assessed the neuropsychological outcome of surgical treatment of epilepsy based on the ratio of deterioration and improvement of cognitive functions. The authors found that this ratio for left hemisphere operations for verbal memory was 44 and 7%, visual - 21 and 15%, nominative speech function - 34 and 4%, speech fluency - 10 and 27% and attention - 6 and 10%, and in right hemisphere operations it was 20 and 14% for verbal memory, 23 and 10% for visual memory, 0 and 4% for nominative speech function, 21 and 16% for speech fluency, and 2 and 15% for attention. According to subjective assessment, regardless of the side of the operation, 9% of patients noted a deterioration in cognition, and 18% indicated its improvement. At the same time, the authors noted a discrepancy between objective and subjective assessments of the dynamics of cognitive functions, in which subjective improvement was determined by patients in cases where objective methods revealed their decline (for example, verbal memory and speech function). Another meta-analysis conducted by the Department of Neurosurgery [71] indicated that patients undergoing epilepsy surgery had better self-rated cognitive function than those receiving medical treatment.

C. Helmstaedter et al. [80] in a long-term study examined the cognitive function of patients with epilepsy, comparing adult patients with drug-resistant epilepsy who underwent temporal lobectomy with control patients who received pharmacotherapy. Memory decline was observed in both groups, but patients in remission, achieved primarily through surgery, were more likely to recover memory within 1 year. Unsuccessful surgical intervention, especially in the case of left-sided resections, on the contrary, accelerated the decline in memory. Predictors of a beneficial effect on cognitive impairment in the postoperative period, according to the authors, were the achievement of complete control over epileptic seizures and an initially higher level of cognitive functioning.

A number of comparative studies [68, 81] devoted to the analysis of the effect of surgical and non-surgical treatment of epilepsy on cognition indicators provide opposite data indicating a deterioration after surgery in immediate semantic memory, delayed recall, memory productivity and verbal reproduction.

The results of domestic studies [82, 83], assessing cognitive functions before and after surgical treatment of epilepsy, indicate that the development of postoperative cognitive disorders, represented mainly by aphasia and decreased auditory-verbal memory during interventions on the left temporal lobe or visual dysmnesia during right-sided operations, are compensated within 12 months. It is worth noting that, according to V.R. Kasumova et al. [82], diffuse neuropsychological symptoms determined in the preoperative period are a predictor of insufficient effectiveness of surgical treatment of epilepsy, while unilateral neuropsychological disorders, on the contrary, improve the prognosis of surgery. The same point of view is shared by M. Perry and M. Duchowny [84], noting that in cases of complete remission after surgery, restoration of cognitive functioning may take years. At the same time, withdrawal of pharmacotherapy is an additional factor contributing to the restoration of cognition. However, as the authors point out, if surgical treatment of epilepsy fails, existing cognitive disorders may worsen or new ones may arise.

Thus, most authors noted a close connection between the success of surgical intervention in terms of controlling epileptic seizures and the subsequent level of cognitive functioning of patients. Factors that have a negative impact on cognitive functions after surgery include additional damage to brain tissue, postoperative complications, the functional significance of resected areas, installation of deep electrodes in non-resected areas of the brain, absence of changes on MRI, bilateral brain damage (for example, sclerosis of both hippocampus), as well as severe cognitive disorders identified during presurgical preparation [76].

The effect of surgical treatment of epilepsy on mental disorders (current data)

A huge number of studies [85–90] indicate that the incidence of mental disorders in patients with epilepsy is several times higher than the incidence in the general population. Symptoms such as depression, anxiety, fear, emotional lability, mania, confusion, hallucinations, and delusions can occur both within and outside of an epileptic attack [90–92]. The results of some studies have shown similar etiological factors in epilepsy and schizophrenia [93, 94], temporal lobe epilepsy and mood disorders [95], epilepsy and bipolar affective disorder [96]. Mental disorders in epilepsy, according to some authors, may be a consequence of the side effects of anticonvulsant therapy [97, 98], as well as provoked by factors such as fear of a seizure or stigma [99].

Despite the recognition of the high prevalence of mental disorders in epilepsy, as well as information contained in a number of studies about the negative impact of preoperative psychopathological symptoms on the results of surgical intervention, this issue is poorly covered in the literature. Most surgical centers do not evaluate the mental status of every patient preparing for surgery. Only patients with an obvious burdened psychiatric history or in case of presentation of relevant complaints in the preoperative or postoperative period are selectively referred to psychiatrists. Thus, according to A. Kanner and S. Schachter [100], out of 88 epileptology centers, only 10 performed a routine psychiatric examination of each candidate for surgical treatment of epilepsy and 3 - in the case of a complicated medical history. It is worth noting that even the recently published practical guidelines, which contain high requirements for centers engaged in the surgical treatment of epilepsy, do not insist on the mandatory inclusion of a psychiatrist in the process of examination and treatment [101], and when assessing the work of such centers, a psychiatrist is not even mentioned in the structure of the interdisciplinary brigades [102]. In domestic clinical recommendations for preoperative examination and surgical treatment of patients with drug-resistant forms of epilepsy [41], although they describe the need for neuropsychologists to assess “personal characteristics, as well as the current state - in particular, the depth of anxious and depressive experiences,” but not a word is said about the role of the psychiatrist in the structure of preoperative examination and postoperative management of patients.

Studies that have studied the psychiatric aspects of surgical treatment of epilepsy are methodologically imperfect and characterized by low quality of design and level of evidence (uncontrolled, open and retrospective with level of evidence VI), and their results, according to H. Altalib [103], require additional evidence base. Let us dwell on the main ones, which consider this problem in two aspects: the influence of current or preoperative mental disorders on the frequency of epileptic seizures after surgery and the effectiveness of surgical intervention in terms of reducing mental disorders.

Some authors [104–109] note a decrease in the likelihood of achieving seizure control if patients with epilepsy have a history or current state of mental disorders. Thus, the results of a 2-year prospective study [109], which followed 434 patients with refractory epilepsy who underwent surgical treatment, using a semi-structured interview to assess mental disorders according to DSM-IV, showed that the prognosis of surgery in terms of seizure control was significantly degree depended on the presence of mental and/or personality disorders identified as a result of presurgical preparation. At the same time, as the authors note, factors related to the underlying disease (age of onset and duration of epilepsy, side of resection, or the presence of mesotemporal sclerosis) did not affect the effectiveness of treatment.

Other authors [103, 110–114] consider the role of mental pathology in the effectiveness of controlling epileptic seizures after surgery to be insignificant. Thus, the results of a 5-year multicenter prospective study [103], which included 379 patients with refractory epilepsy, using the structured diagnostic interview CIDI showed that neither depressive nor anxiety disorders had a significant effect on the outcome of surgery in terms of seizure control. However, this study did not include patients with psychotic disorders and did not assess personality disorders or epilepsy-specific interictal dysphoric disorder [115].

Some studies (usually uncontrolled) indicate that surgical treatment of epilepsy either does not affect current mental disorders [116] or leads to their improvement [117–121]. Thus, as a result of a 6-month comparative study in which patients with refractory epilepsy who underwent surgical treatment were examined with a group of patients undergoing drug therapy, it was shown that anxiety and depression scores on the HADS scale and the total number of positive responses on the SCL scale -90-R were lower in operated patients [120]. According to the same study, patients in the control group showed a tendency toward an increase in the occurrence of de novo

, while operated patients were somewhat more likely (the differences are statistically insignificant) to achieve remission for affective, anxiety and psychotic disorders. A limitation of this study was the exclusion from the analysis of patients with combined epileptic and psychogenic non-epileptic seizures, as well as the lack of diagnosis of personality disorders.

Some studies [107, 122, 123] have different conclusions: mental disorders may arise or worsen after successful surgery to control epileptic seizures. For example, a systematic review conducted by S. Macrodimitris et al. [124], demonstrated that the likelihood of developing mental disorders after epilepsy surgery varies from 1.1 to 18.2%. A retrospective study [107] involving 280 patients undergoing epilepsy surgery assessed the dynamics of mental disorders 4 years after surgery. Diagnosis was made based on DSM-IV criteria, taking into account psychogenic nonepileptic seizures and epilepsy-specific postictal psychoses. Mental disorders after surgery occurred in 38% of patients, of which approximately 50% occurred for the first time. Among the risk factors for the development of mental disorders after surgical treatment of epilepsy, V. Vakharia et al. [76] identify the main ones, which include poor control of seizures, a history of mental pathology, as well as secondary generalized seizures.

Thus, this review of modern studies devoted to the analysis of the dynamics of the frequency of epileptic seizures, mental and cognitive disorders in patients with intractable epilepsy after surgical treatment contains ambiguous and sometimes contradictory results from uncontrolled and controlled studies. Mental disorders are not a contraindication to surgical treatment of epilepsy, especially since there is a possibility of improvement in the mental state of patients when seizure control is achieved. The need for further prospective controlled studies assessing the bilateral relationship between surgical treatment of epilepsy and mental disorders, taking into account their impact on cognitive functions and quality of life of patients, is dictated by the needs of improving practical approaches to optimizing presurgical preparation, developing algorithms for postoperative management of patients depending on the combination of epileptological, cognitive , psychiatric and social outcomes of surgical treatment of epilepsy.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Surgical treatment of epilepsy

In most cases, epilepsy does not require surgical treatment. However, if conservative therapy is ineffective, a change in strategy is required. To localize the lesion, EEG video monitoring and other diagnostic methods are used, which allows you to accurately select the appropriate intervention technique. Surgical treatment is prescribed mainly for focal epilepsy, since only one part of the brain is affected, which is removed. In addition, for some types of disease, hemispherectomy and callosotomy are possible.

Another effective treatment for epilepsy is neurostimulation. It is based on the introduction of a special device that activates the vagus nerve and stimulates the brain. Used as a supplement.

First aid

It is important for relatives and friends of a person suffering from epilepsy to know the rules of first aid. Often the outcome of an attack depends on the actions of the people around you.

Providing first emergency aid should include the following actions:

- If there are warning signs of an attack, the person should be placed on his back and freed from tight clothing.

- Turn the person's head to the side. This is necessary to avoid tongue retraction and saliva aspiration.

- If vomiting develops, keep the patient (without excessive force) in a position on his side, preventing his head from falling back.

- Do not use surrounding objects (cutlery, spatula) to unclench your jaw during an attack.

- Do not give the person medications or liquids during an attack.

- Isolate the patient as much as possible from objects that pose a threat to him (sharp corners, piercing and cutting surfaces).

- Maintain silence and avoid sudden and loud sounds. Record the duration of the attack. If this happens for the first time, it is advisable to record it on video.

- Stays nearby until the symptoms of the attack completely stop.

- Do not touch the patient after the seizure is over. If a person falls asleep, let him sleep.

- Measure body temperature (relevant for children with high body temperatures).

If the duration of the attack exceeds 3 minutes, and the ambulance has not yet arrived, it is necessary to give the patient a drug prescribed by a doctor for the treatment of epilepsy, if the diagnosis has already been made earlier. It is important to use it rectally as oral use is unsafe.

Genetic studies when choosing a treatment method for epilepsy

To make an accurate diagnosis, in addition to electroencephalography and magnetic resonance imaging, genetic studies are widely used. They are prescribed when a history of disease is detected and may include:

- conducting tandem mass spectrometry to identify inborn metabolic disorders;

- karyotype studies;

- HMA;

- high-throughput sequencing.

Research will allow you to accurately identify the cause of the disease and determine the further prognosis.