Irritation of the cortex covering the deep structures of the brain is a natural process that normally occurs as a result of exposure to external factors, which forces the central nervous system to react and form a physiological response. Pathologies of nervous structures provoke disturbances in the functioning of the brain, which is reflected in irritation (irritation) of its parts without the influence of external stimuli. This condition leads to malfunctions in all body systems. Diagnosed at any age, regardless of the person’s gender.

Definition of pathology

Irritative disorders arise due to disruption of the transmission of nerve impulses, which provokes a deterioration in brain activity. Irritation of the cortex covering the brain is a pathological condition that is manifested by the spontaneous appearance of a focus of irritation in a certain area, which leads to the appearance of characteristic symptoms. An example of a normal reaction of the nervous system to an external irritant is a decrease in pupil diameter in response to bright light, which occurs as a result of irritation of the optic nerve.

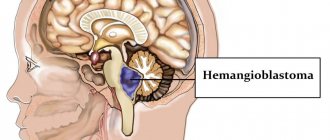

Spontaneous irritation without obvious reasons is a pathology that significantly complicates a person’s life. Irritation of areas of the brain is not included in the international list of diseases ICD-10, because more often irritation of the cortical, median (deep), diencephalic structures is a symptom of the primary disease. Among the pathologies manifested by similar symptoms, it is worth noting a tumor localized in the brain tissue, organic damage to the nervous tissue of various etiologies.

There are focal (irritation of a local area of the cortex) and diffuse (pathological process spreads throughout the entire cortex) irritation of cortical structures. The pathological condition may be accompanied by specific symptoms or be asymptomatic. Irritation of stem structures, which include the trunk, mediobasal and intermediate sections, leads to dysfunction of the brain and body. Failures manifest themselves in the form of syndromes of neuropsychological and autonomic origin.

Irritation in the area of diencephalic structures, which includes the thalamus, hypothalamus, pituitary gland and other parts of the brain, is a pathological condition, often manifested by decreased self-esteem, sudden mood swings, apathy, and increased fatigue, which indicates behavioral and psycho-emotional disorders.

Treatment tactics

Having identified irrational changes in a person, experts strive to eliminate their main cause - the focus of excitation in the cerebral cortex. As a rule, these are vascular defects, tumors, consequences of injuries, cysts. Whenever possible, surgical excision of the affected areas is performed.

If the irritation of the cortex was provoked by viral, infectious processes, then complex therapy includes:

- antiviral agents - Acyclovir, Kagocel, Ingavirin, Amiksin;

- antibacterial agents - a subgroup of protected penicillins, third generation cephalosporins;

- anti-inflammatory medications - non-steroidal drugs, for example, Nimesulide, Meloxicam, Airtal;

- To stop convulsive attacks, drugs from the subgroup of modern anticonvulsants - Apilepsin, Diphenin, Finlepsin - will definitely be selected.

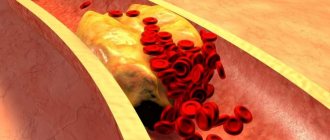

Up to 2/3 of cases of irritation occur due to atherosclerotic lesions of the brain. Therefore, the complex of medications should contain statins - drugs that reduce cholesterol levels in the cerebral vessels. These will be the tablets “Rosuvostatin”, “Mertinil”, “Atoris”, “Torvacard”.

In order to improve cerebral circulation, courses of nootropic medications are required - Cerebrolysin, Actovegin, Cavinton, Piracetam. In order to strengthen memory, psychologists and psychotherapists will conduct sessions with the person.

Only with early treatment and comprehensive modern treatment can one cope with irritative disorder. Therefore, you should not delay consulting a neurologist - at the first symptoms of neurological deterioration, you must immediately make an appointment with a doctor.

Causes

The pathological condition can develop as a complication of somatic diseases - measles, chickenpox, rubella, malaria. Such disorders can be provoked by an increase in intracranial pressure due to various reasons. Reasons for irritative changes include:

- Traumatic brain injuries.

- Infectious diseases affecting parts of the brain (meningitis, encephalitis, abscess, arachnoiditis).

- Tumor processes and other space-occupying formations in the cranial cavity (cysts, foci of hemorrhage).

- Demyelinating diseases, including multiple sclerosis.

- Lesions of the vascular system supplying brain tissue (atherosclerosis, TIA - transient cerebrovascular accident, embolism - blockage of a vessel, ischemic, hemorrhagic strokes).

- Neurodegenerative diseases.

- Violation of metabolic processes.

- Intoxications occurring in acute and chronic forms (chronic alcoholism, chemical poisoning).

Among the provoking factors, it is worth noting alcohol abuse, drug use, stress, excessive mental, mental, physical stress, living in a region with an unfavorable environment. Often, such disorders occur during pregnancy, as a consequence of hormonal changes against the background of existing organic brain damage.

Main features

Dysfunction of the middle (deep) sections is often manifested by attacks of general weakness, a feeling of suffocation, dizziness, malaise, unmotivated fear, changes in pulse and blood pressure. These symptoms are similar to those of epilepsy and reflect the process of irritation of brain structures. Irritation of the cortical parts is more often manifested by behavioral deviations without pronounced neurological symptoms. Symptoms caused by the disorder depend on the location of the source of irritation:

- Frontal zone. Manifestations: motor dysfunction, twitching of the head and visual organs. When the adversive field is damaged, convulsions occur, often with confusion and loss of consciousness at the beginning of the attack.

- Temporal zone. Accompanied by auditory hallucinations. Damage to the opercular region initiates involuntary swallowing and chewing movements.

- Occipital zone. Manifestations: visual hallucinations, photopsia - the appearance of foreign objects in the field of view (dots, lightning, spots, lines).

- Parietal zone. It manifests itself as a sensitivity disorder - numbness, tingling, impaired perception of cold and hot objects, a change in the pain threshold. Damage to the central gyrus area is accompanied by epileptic seizures, which at the initial stage affect the muscles of the face and limbs.

- Cranial fossae. Manifestations: visual and auditory dysfunction, trigeminal neuralgia (affecting the trigeminal nerve), olfactory disorder.

Signs of cortical irritation with diffuse damage to multiple areas of the brain include convulsive syndrome. Convulsions develop according to the myoclonic type, regardless of the state (rest, movement) in which the patient is. Cortical myoclonus is characterized by a short-term, rapid course. At the same time, absence seizures—minor epileptic seizures—may occur while maintaining normal muscle tone. Grand mal epileptic seizures develop according to the following scheme:

- Aura. Headache, sleep disturbance, feeling unwell several hours or days before the attack.

- Phase of increased muscle tone. Loss of consciousness and balance. Synchronous, simultaneous contraction of muscles in the entire body. Duration – about 60 seconds.

- Clonus phase. Unsynchronous, chaotic contraction of body muscles. Duration – about 2 minutes.

After a seizure, the muscles relax and the patient falls into deep sleep. Upon awakening, the patient is often disoriented regarding space and time. He may have retrograde amnesia (cannot remember events preceding the attack). Signs of irritation in the area of diencephalic (deep) structures that make up the brain include epileptic seizures, deterioration of cognitive abilities, speech dysfunction, disorders of the autonomic nervous system, and psycho-emotional disorders.

Irritation in the area of the stem structures at the bottom of the cranium is accompanied by such disorders as confusion, disturbance of sleep and wakefulness, deterioration of memory and concentration. Irritation of the hypothalamic structures that make up the central parts of the brain is accompanied by the following symptoms:

- Malfunctions of the autonomic nervous system.

- Depressive state.

- Deterioration of attention and memory functions.

- Psychopathic disorders with symptoms characteristic of Korsakoff psychosis (retrograde amnesia, ataxia, disorientation, behavioral disorders).

Irritation in the area of the hypothalamic regions often initiates a deterioration in cognitive abilities, reversible speech dysfunction, and a change in personal perception of the position of parts of the torso and the entire body in space.

The duration of attacks is from 2 to 6 months, rarely longer. The condition begins with a change in general behavior, the appearance of capriciousness, self-will, callousness and cruelty in relations with parents. Hysteroform reactions arise periodically, and duality is revealed in desires. Sensitivity to loud sounds, comments, changes in environment increases, appetite changes, falling asleep becomes more difficult, and awakening becomes earlier. Some patients experience movement disorders in the form of monotonous movements that have lost their purpose: these are movements of the head, shoulders, hands and more complex movements associated with pulling up clothes. The movements are repeated many times a day and lead to increased general anxiety. If children's attention is fixed on movements, then they can refrain from performing them for some time, although they often do not realize the futility of the actions they perform.

Aimless movements at this age are easily automated, acquire a pathologically habitual character and are usually then almost unnoticed by children. In a number of observations, movements of an obsessive nature arise; in such cases, children can determine that they “want to, but cannot restrain them,” that “movements bother them.” Many children experience hyperkinesis and tics.

In most patients, the clinical picture is supplemented by anxiety, fears, and night terrors. The night's sleep is interrupted by crying. When children wake up, they show anxiety and hide. When questioned, they confirm that they are “scared.” During the daytime, fear of the dark, your bed, cars, new surroundings, and people is possible. Abstract fears of smoke, shadows, clouds, etc. easily appear. Fear usually arises when confronted with the object of which they are afraid. By nature, fears can be either monomorphic with a monotonous theme, or polymorphic. Groundlessness, disconnection from the external situation, and recurrence of fears are observed in all patients. Many children are able to sense their foreignness.

Attacks of this type of atypical childhood psychosis are characterized by obsessive questions. Physiologically conditioned by age questions in such states lose their cognitive meaning and are senselessly repeated by children many times, without interest in the essence of the answer. In some cases, a monotonous repetition of empty rhyming neologisms occurs. Sometimes there is an obsessive demand for a specific, one and the same answer. With the advent of a feeling of alienation of obsessions, obsessive rituals of a protective nature arise: “In order not to get infected, you need to wash your hands several times, count your buttons,” etc. In the evening hours, obsessions intensify. Some children refuse to sleep, explaining it with fear that thoughts will interfere with them and they will not be able to fall asleep. Then a number of children begin to experience repetitive, monotonous dreams that frighten them. In the same conditions, senestopathies are possible in the form of stabbing, unpleasant, painful sensations (“stabs in the arms, legs... shoots...”, “arms, head hurt,” etc.).

In attacks at the height of the state, selective mutism may appear with a refusal to answer questions from strangers, and often from relatives. When trying to answer, children grimace, move their tongues, but do not speak. Encouragement and persuasion enhance these phenomena. In some cases, as the condition worsens, symptoms of speech regression appear, and babbling and tongue-tied pronunciation of sounds returns. Ideational inhibition is often combined with general inhibition; the angularity of movements, mannerisms, and awkwardness increase. Vegetative symptoms are significantly pronounced: sweating, coldness of the skin of the hands and feet, paleness of the face, discomfort in the heart area, nausea. With prolonged attacks, behavior becomes monotonous and monotonous. The game is simplified, a refusal of toys, and the egocentric nature of games “to oneself” are observed. Children refuse to communicate with peers and relatives, and are immersed in the world of autistic fantasies of primitive content. Behavior is stereotyped, children protest against changes in room, regime, clothing, food and lead the life of recluses.

Clinical, dynamic and follow-up observation of a large group of patients with childhood autism of procedural origin revealed two series of disorders: positive - catatonic-regressive, catatonic, polymorphic, anxious-affective and negative - in the form of distorted or delayed autistic dysontogenesis. In 3/4 of cases of childhood procedural autism, after 6-24 months from the onset, positive symptoms begin to subside. In the clinical picture, symptoms of distorted, delayed development come to the fore. These are the so-called acquired, deficit autistic conditions. The clinical picture in them is to some extent similar to the clinic of constitutional or developmental-processual autism of the Asperger or Kanner type. Depending on the premorbid characteristics of the child’s personality, the severity, depth of negative and positive circle disorders, and their extent, the following variants of autistic deficit acquired conditions are possible.

The first type of acquired autistic deficit condition in childhood procedural autism is determined by the features of psychophysical infantilism, the loss of previous capabilities - the impoverishment of higher mental, emotional and volitional personal properties. Activity and energy level are reduced, motivations are insufficient, interests are immature. Communication with peers is difficult. Autistic withdrawal is always characteristic. Even with an impoverished inner world, persistent, pretentious autistic interests and games are possible.

Children have difficulty acquiring knowledge. At school age, learning is usually duplicated due to lack of communication and especially personal distortion. Such children are often transferred to individual education in mass or specialized school programs.

These conditions are characterized by wave-like changes in activity, asthenic disorders, acquired phase-affective disorders, obsessions, psychopathic manifestations, and residual disorders of the catatonic register.

The symbiotic relationship with the mother persists throughout almost the entire life, especially if it is not replaced by a connection of a similar type with a person of the opposite sex (the latter is usually initiated by the parents of the autistic person).

The second type of acquired personality changes in childhood procedural autism is determined by the features of disharmonious infantilism. The premorbid physiologically predetermined line of personal development changes sharply. The normal degree of maturity is not achieved. Attachments are weakened, and a symbiotic-indifferent relationship with the mother remains for many years. Characterized by emotional dullness with a loss of brightness and liveliness in feelings, the appearance of a psycho-aesthetic proportion in feelings such as “wood - glass”. Incentives are insufficient. There is a pronounced deficit in communication and communication skills. Speech has been modified.

The activities reveal pedantry, rigidity, and stereotyping. Autistic hobbies are of a poor nature with an infantile theme. Hobbies often take on the character of autistic, one-sided drives that replace purposeful activity. Learning suffers. The scope of interests is narrowed. The stock of knowledge sharply lags behind the age norm. Associations are loosened, often with features of fragmentation, and difficulties are found in expressing thoughts and school material. Psychopathic behavioral traits and residual positive disorders are possible.

The third type of acquired personality changes in childhood autism of procedural genesis is determined by an oligophrenia-like defect with autistic behavior. Cognitive activity is sharply limited. Speech is lost or egocentric in nature. Communication with relatives is established at an indifferent or symbiotic level. The emotional sphere is underdeveloped. Behavior is stereotypically monotonous, with play at a protopathic level. Instinctive drives can be reduced or enhanced. Self-service skills have not been developed. Communication at the verbal, gestural, and eye levels is lost; Most often, easily depleted communication is preserved at the tactile level. Gross and fine motor skills are dissociatedly immature, mannered stereotypies in the fingers are preserved, and generalized motor revitalization is observed in cases of increased activation of the child.

Catatonic and catatonic-hebephrenic disorders, fears, and deceptions of feelings at a primitive level are relevant and periodically intensifying.

So, in the case of childhood autism of procedural genesis, it is preceded by a stage of normal development of the child, then a period of psychosis of a complex positive-negative structure, after which an acquired autistic deficit state is formed. These acquired autistic deficit conditions vaguely resemble autism of the Asperger and Kanner types. Since the symptoms of impaired development and positive symptoms of the psychotic series are very closely intertwined and in children under the age of 5-6 years are difficult to differentiate, these conditions in Russian psychiatry retain the name - childhood autism of procedural genesis, according to ICD-10 (1994) - childhood autism, or atypical autism, not only at the developmental stage of psychosis, but also at its remote stages. As noted above, the deontological aspect of such verification of a state is also taken into account. We believe that it is more correct to make a diagnosis of childhood schizophrenia after a certain age period, after 8-10 years. This approach is followed in child psychiatry by specialists in most countries.

We present a number of clinical observations of patients with childhood autism of procedural origin.

Observation 1. Clinical example of a patient with childhood procedural autism (with onset before 3 years of age).

Patient S., born in 1980. Heredity: maternal grandmother committed suicide at the age of 47. History: child from the 1st pregnancy, which occurred with toxicosis in the first half. The birth is physiological, on time. Body weight - 2700 g, length 48 cm. He immediately screamed. He was discharged from the maternity hospital on the 6th day. Until 1 month he was breastfed, after that he was bottle-fed. Constipation, restlessness, and frequent crying were noted. Early motor development: holds head from 3 months, sits from 6 months, crawls (only backwards) from 8 months, walks from 12 months. At 14 months he began to crawl again, after which he walked independently by the age of 2 years. Early speech development: cooing from 3 months, babbling from 8 months, first words from 10 months. By the age of one year he knew 10 words, then he fell silent and began to speak individual words at 2.5 years, simple phrases from the initial syllables of words - at 3.5 years. He grew up as a “comfortable child” for his mother, did not want to be held, and spent hours lying alone in his crib. Previous illnesses: from 3 months to 1 year, 3 months - frequent acute respiratory infections with an asthmatic component, then he was rarely ill. From the age of 12 months, he played with his fingers for a long time, brought them close to his eyes, twirled rattles and lids, but more often than not he simply threw them out of the bed. From the age of 1.5 he crawled from corner to corner of the room, moving cars. At the same time, sometimes he put his head on the floor, raised his lower body up and crawled in this position for hours.

At the same age, I began to be afraid of the noise of cars, trains, TV, and vacuum cleaner. He did not strive for children, even if he was led to them, he did not notice them. The game remained primitive, monotonous, with everyday objects. He leafed through the books, not paying attention to the pictures. More often he tore them into strips, threw them on the floor, knelt down and moved the strips of torn paper with his head. He used syllables of words only at moments of emotional stress. At 3.5 years old he began to talk to himself. The vocabulary gradually accumulated; words did not correlate with objects. He was sent to the village to live with his grandmother, and calmly endured the separation from his mother. Throughout the year, his condition remained monotonous, he became physically stronger, and stopped suffering from somatic diseases.

At the age of 4 he was placed in kindergarten, did not adapt well, did not let his mother go, and did not take part in classes. Stayed away from children. The teachers tried to address him with “command words.” He did not react immediately, he was delayed, but more often he followed orders. Rarely uttered the word “mother.” On the recommendation of the pediatrician, due to a significant lag in mental development, they turned to a neuropsychiatrist. Diagnosis: early childhood autism. I received etaparazine, cyclodol, Cavinton, a mixture with magnesia, citral and bromine. They recommended classes with a speech pathologist. At the age of 5, a medical-pedagogical commission refused to allow him to attend a specialized kindergarten for children with mental retardation. From 5 to 7 years old I studied privately with a speech therapist. I began to memorize quatrains, pronounce out loud the endings of phrases from them, and then entire phrases. He often resorted to sign language. I still played alone, monotonously. I identified the primary colors and compared them. At the age of 6.5 years, fears arose, and therefore he was admitted to a day hospital for children with autism at the National Center for Children with Autism of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences.

Mental status.

When parting with his mother, he cried, his mood was unstable during the day, he stayed close to the staff, away from the children. Manipulated the toys offered to him. Gradually I got used to the separation. He approached the doctor without asking questions, looked into the distance, and sometimes observed what was happening. He answered questions after pauses, in monosyllables or in phrases of two or three words, omitting the subject. He couldn’t stand confined spaces, he screamed, his face was distorted with a grimace of fear when the doors to the room were closed. During classes, I had difficulty remembering the names of household items depicted in the pictures, and confused the names of animals. He distinguished colors, mechanically counted to 10. He folded cut pictures from 3 parts. Periodically, speech became quiet, slurred, and went “inward.” He spoke with infantile, lisping intonations. Fine movements in the fingers were not sufficiently formed; he grasped objects with the entire hand, did not place mosaics in their sockets, and did not hold pencils. He served himself poorly, his neatness skills were formed.

During the first weeks, his mood improved and became elevated, he ran back and forth in the playroom, shook his hands, laughed at something, and could not tolerate physical contact. Speech often became mumbled, neologisms and echolalia arose easily. The staff’s requirements were fulfilled after repeated repetition of the same requests, and often after a visual demonstration of the necessary actions. He was indifferent to approval and praise. Gradually I became accustomed to the routine of the department. Coordination of movements improved, mastered basic self-care skills (learned to brush teeth, wash, tie shoelaces, fasten buttons, eat independently, etc.). Orientation in the everyday situation has expanded. I used speech more. He preferred to be close to children, watched them play, at times obeyed them, and allowed himself to be used in the game “like a living toy.” The mood has leveled off. The fears are gone. Did you sleep well. I visited the day hospital with desire.

Somatic status:

correct “gracile” physique, short, low nutrition. For organs without pathology. No pathology was noted in blood and urine tests or biochemical blood tests.

Neurological status:

Congenital compensated hydrocephalus and mild extrapyramidal disorders were revealed.

Speech therapist consultation:

vocabulary is grossly reduced, generalizing concepts are not sufficiently formed; speech - slurred, phrases with ungrammaticalisms; in words of contamination. Phonetic-phonemic underdevelopment of level I speech was noted.

Consultation with a psychologist:

a deep dissociated delay in intellectual development was revealed, the level of motivation was reduced, and the voluntary regulation of activity and attention was impaired. Inertia and perseverativity were revealed in mental processes. Emotionally impoverished. Learning ability is significantly reduced. It is recommended to try training in the auxiliary school program.

EEG:

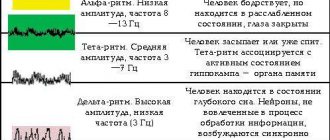

signs of increased irritation of the cortex and deep brain structures. -waves predominate, 1-band decreases.

X-ray of the skull

- without features.

Consultation with an ophthalmologist:

fundus without pathology.

Treatment:

stelazine, etaprazine, cyclodol, sonapax, lithium carbonate, cogitum, nootropil.

Recommended:

training according to the auxiliary school program (imbecile class from 9 years old), supportive therapy: etaparazine, cyclodol, glycine, cogitum.

Conclusion.

The child suffered infantile psychosis with catatonic-regressive disorders in the 1st—2nd year of life. At the last observation, we can talk about an acquired autistic deficit state. The clinical picture is determined by mental underdevelopment of the oligophrenia-like type (with unevenness and chaos in the main functional systems: speech, motor skills, play activity, etc.); insufficiency of the emotional-volitional sphere; weakness of motives; autistic isolation from the outside world.

Observation 2.

Patient A., born in 1989, suffers from childhood procedural autism (with onset between 3 and 6 years). Heredity is not burdened with manifest psychoses. A child from the 1st pregnancy, which occurred with toxicosis in the first half. Childbirth on time, physiological. Body weight 3200 g, length 50 cm. He immediately screamed. I was put to the breast on the 2nd day and sucked actively. He was discharged from the maternity hospital on the 5th day. In infancy he was restless. Early psychomotor and speech development is timely. He singled out his mother early. By the age of 2, he spoke in extended phrases and used first-person pronouns to refer to himself. After a year I played with children and loved cars. By that time, the skills of neatness and self-service had already been formed. By the age of 3, he enjoyed studying with his mother, learned all the letters, distinguished colors and shapes of objects, and asked to read books to him. He loved order, and after playing he put the toys back in their place.

At the age of 4, he autochthonously lost interest in activities, his memory deteriorated, and he became protestful. He began to talk about himself in the second and third persons, “he wants.” He began to speak less, his phrases gradually became simpler, his answers became monosyllabic, and he began to resort to gestures. He used speech less and less as a means of communication with others, spoke to himself, and muttered sounds. He did not let his mother go, avoided the children, covered his ears if they turned to him with questions. There was a fear of cars. I sat in one place for a long time without playing. By the age of 5 he began to “come to life”, began to speak again, play with cars, and build with blocks. He quickly became exhausted, became distracted and destroyed what he had built. I only walked with my mother. At the age of 6 he entered the day hospital for children with autism at the National Center for Children's Health of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences.

Mental status.

He was brought into the department with persuasion, cried, did not let his mother go, constantly asked about her, looked for her. He ran in circles around the playroom, did not play with anything, avoided children, hid in any corner. He did not answer questions or switched to sign language. He covered his ears with his hands and was extremely negative. At times he became detached, his gaze went to the side, and it seemed that he did not hear the speech addressed to him. But with severe stimulation, he could immediately answer in monosyllables, used pronouns in the second and third persons in relation to himself, often switched to a whisper in his answers, and then the speech completely went inside. It was difficult to determine his stock of knowledge and interests. Only after 4 months of therapy, I got used to the routine of the department and began to let go of my mother. He calmly came to the group and immediately hid in a corner, from there he watched what was happening. Left to his own devices, he could not occupy himself with anything, he manipulated the toy, played with his fingers, and brought them close to his eyes. I studied only when I was left alone with the teacher. Over the next 2 months, the condition remained unstable, a low mood prevailed, he refused to study, covered his ears, ran around the department, and shook his hands. His appetite remained selective, but he began to eat on his own. Gradually he began to sleep during the daytime, in his free time he spoke more to himself and more often responded in one word to those around him. Even later, he took part in group classes and began to use extended phrases in his answers. The mood has leveled off. I began to remember what I had lost and acquire new knowledge.

Somatic status.

Physical development according to anthropometric data is below average. No pathology was detected in the organs. Biochemical blood tests - no pathology, tests for HIV, HBS - negative.

Consultation with a neurologist

— there is no data for the current neurological process.

X-ray of the skull.

The shape and size of the skull are normal. There are no bone changes in the vault. Turkish saddle of regular shape and size. There is no M-ECHO bias. Indications for intracranial hypertension.

Oculist.

The fundus is without pathology.

EEG: regulatory disturbances in the form of an increase in the frequency of the -rhythm and an increase in the index (3-activity. Signs of cortical irritation. No typical epiactivity was detected.

Speech therapy examination.

Upon admission, he had a negative attitude towards verbal instructions. A few weeks later, I began to compose phrases of 2-3 words according to instructions. Often with inaccurate use of verbs. I couldn’t compose a story based on a series of plot pictures. He knew individual letters, but did not put them into syllables. General speech underdevelopment (GSD) level II and dissociation of speech development were diagnosed. Before discharge, his condition improved. In group classes, contact with children and communication remained difficult; it was better to study individually. The subject and verb vocabulary has expanded. A clear systematization of generalizing concepts has emerged. Based on questions, he composed phrases well. When analyzing a simple text, he answered in monosyllables. Echolalia was preserved in spontaneous speech.

Psychological examination.

Depressed mood prevails. In a communication situation, he shows irritability and negativity. He rarely communicates, mainly with children on a tactile level. In the game he is not emotionally captivated, acts formally, and learns to obey the rules.

Conclusion.

The clinical picture reveals erased catatonic symptoms (active negativism, monotonous stereotypical walking back and forth, inactivity, mannered stereotypical movements in the fingers, echolalic speech). Depressed mood. Mental development in premorbidity is high and advanced. The personality structure included autistic traits, pedantry, symbiosis with the mother, and limited communication with children. In the period of 3.5-4 years, the first changes in the condition were noted: autism deepened, fear periodically arose, the consciousness of the “I” was disturbed, speech changed, manege walking appeared, behavior became stereotypical, interest in activities disappeared. Then the condition was determined by catatonic-regressive manifestations. Currently, the formation of remission is observed. Diagnosis: early childhood autism of procedural origin (atypical psychosis, according to ICD-10).

Therapy was carried out sequentially with Eglonyl, amitriptyline, etaprazine, stelazine with cyclodol, cogitum, and multivitamins.

He was observed at his place of residence by a psychiatrist. He received maintenance therapy with finlepsin, stelazine, cyclodol, and glycine. I studied individually with a defectologist and with my mother. My vocabulary has increased, I have become more attentive and assiduous. Physically stronger. Played with older children. After the summer holidays, he was re-admitted to the day hospital for children with autism at the National Center for Children with Autism of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences to continue therapeutic and restorative correction.

He entered the group crying, but quickly calmed down, remembering the children and the staff. The mood is unstable. At times he looked away to the side, did not react to spoken speech, walked in circles, and pulled away when someone touched himself. He answered questions in short, blurted phrases; sometimes the speech became egocentric, with echolalia and mannered intonations. Correctly oriented in the surroundings, body diagram, named his first and last name, spoke about himself in the first person. He knew the names of his parents, home address, primary colors, he had access to the concepts of “large - medium - small,” counting in direct order to 10 with visual reference to objects. During his repeated stay in the department, his condition improved significantly, he became calmer, and obeyed the department’s regime. Negativism decreased and I began to actively use speech as a means of communication with others. I served myself, progressed in development, and my subject vocabulary expanded. I comprehended the plot pictures and texts. He had a positive attitude towards classes, but was not always productive. During classes in drawing, appliqué, and modeling, he performed the work with outside help. During music lessons I sang songs along with all the children. I read poetry in a quiet voice.

He received maintenance therapy: stelazine, finlepsin, cogitum, glycine, multivitamins.

Follow-up:

9 years. Studying under the auxiliary school program. Reads syllables, performs mathematical operations within 5. Goes with his mother to the store, can buy bread and sweets there with her help. Watches cartoons, listens to books read. Plays with children. All the child’s activities take place under the guidance and encouragement of the mother. There are no productive psychopathological symptoms.

The condition can be defined as deficient after suffering a catatonic-regressive attack; an oligophrenia-like defect with autistic forms of behavior, impaired communication, and insufficiency of the volitional sphere was formed.

So, throughout the history of the study of endogenous psychoses in childhood, the following questions have been discussed. Does psychosis manifest itself in childhood as it does in adulthood? Can a disorder that is represented only by manifestations of developmental disorders be considered psychosis? Are symptoms of negative and positive types equally significant in psychosis in childhood? Due to the presence of two series of pathologies in the clinic of psychosis in childhood, the classifications of these psychoses are constantly being restructured, for example in ICD-9 and ICD-10. To date, in the predominant number of psychiatric schools (France, USA, Great Britain, etc.), endogenous schizophrenic psychosis is considered in the circle of constitutional, symbiotic, infantile disorders, and childhood autism. We consider it possible to adhere to a similar verification in these cases, replacing the name of early childhood schizophrenia with childhood autism of procedural genesis.

Diagnostics

The main diagnostic method is a study in EEG format (electroencephalogram). During the study, bioelectric potentials of brain structures are recorded, which is reflected in certain patterns (waves, amplitude, rhythm). Irritation of brain areas manifests itself as:

- Desynchronization, uneven amplitude of the alpha rhythm.

- Increase in volume in the general structure of oscillations and amplitude of the beta rhythm.

- The appearance of a large number of sharp peaks in the overall wave pattern.

Signs revealed during EEG studies resemble epileptiform changes. To establish the primary causes of disorders, instrumental diagnostics are carried out, which makes it possible to identify the underlying disease. For this purpose, examinations are prescribed in the format of MRI, CT, ultrasound, angiography, positron emission tomography. Neuropsychological diagnostics are carried out to identify the nature and degree of disorders in the emotional, speech, and cognitive spheres.

What does an EEG (electroencephalogram) of the brain show?

EEG helps monitor changes in the brain, both structural and reversible. This allows you to monitor the activity of a vital organ during therapy and adjust the treatment of identified diseases.

Indications for an electroencephalogram

Before prescribing an encephalography to a patient, a specialist examines the person and analyzes his complaints. The following conditions may be the reason for an EEG:

- sleep problems - insomnia,

- frequent awakenings, sleepwalking;

- regular dizziness, fainting;

- fatigue and constant feeling of tiredness;

- causeless headaches.

Insignificant, at first glance, changes in well-being may be the result of irreversible processes in the brain. Therefore, doctors may prescribe an encephalogram if they detect or suspect pathologies such as:

- vascular diseases of the neck and head;

- vegetative-vascular dystonia, disruptions in cardiac activity;

- condition after a stroke;

- speech delay, stuttering, autism;

- inflammatory processes (meningitis, encephalitis);

- endocrine disorders or suspected tumor foci.

An EEG study is considered mandatory for people who have suffered head trauma, neurosurgical surgery, or suffering from epileptic seizures.

How to prepare for research

Monitoring electrical activity in the brain requires little preparation. For the reliability of the results, it is important to follow the basic recommendations of the doctor. Do not use anticonvulsants, sedatives, or tranquilizers 3 days before the procedure. 24 hours before the test, do not drink any carbonated drinks, tea, coffee or energy drinks. Avoid chocolate. No smoking. On the eve of the procedure, thoroughly wash your scalp. Avoid the use of cosmetics (gels, varnishes, foams, mousse). Before starting the study, you need to remove all metal jewelry (earrings, chain, clips, hairpins). Hair should be loose - all kinds of braiding must be unbraided. You need to remain calm before the procedure (avoid stress and nervous breakdowns for 2-3 days) and during it (do not be afraid of noises and flashes of light). An hour before the examination you need to eat well - the examination is not carried out on an empty stomach.

How is an electroencephalogram performed?

The electrical activity of brain cells is assessed using an encephalograph. It consists of sensors (electrodes) that resemble a swimming pool cap, a block and a monitor, where the monitoring results are transmitted. The study is carried out in a small room that is isolated from light and sound. The EEG method takes little time and includes several stages: Preparation. The patient takes a comfortable position - sits on a chair or lies down on the couch. Then the electrodes are applied. The specialist puts a “cap” with sensors on the person’s head, the wiring of which is connected to the device, which records the bioelectric impulses of the brain. Study. After turning on the encephalograph, the device begins to read information, transmitting it to the monitor in the form of a graph. At this time, the power of electric fields and its distribution in different parts of the brain can be recorded. Use of functional tests. This is performing simple exercises - blinking, looking at flashes of light, breathing rarely or deeply, listening to sharp sounds. Completion of the procedure. The specialist removes the electrodes and prints out the results.

How long does the procedure take?

A regular encephalogram is a routine EEG or diagnosis of a paroxysmal state. The duration of this method depends on the area being studied and the application in monitoring functional tests. On average, the procedure does not take more than 20–30 minutes. During this time, the specialist manages to carry out: rhythmic photostimulation of different frequencies; hyperventilation (breaths are deep and rare); load in the form of slow blinking (open and close your eyes at the right moments); detect a number of functional changes of a hidden nature.

Your health is in your hands!

In the LLC “Consultative and Diagnostic Clinic named after E.M. Niginsky" you can undergo an electroencephalogram of the brain.

Reception is conducted by highly qualified specialists.

To make an appointment with specialists and get the necessary information, please call:

+7 or online on the website of the clinic nord - med . ru

Possible contraindications. Specialist consultation required!

Treatment options

Treatment of the pathological condition, which is manifested by general cerebral changes of an irritative nature, is aimed at eliminating its causes. Treatment is carried out for the primary disease that provoked the corresponding symptoms. In case of infection, antibacterial and antiviral drugs are prescribed. Other medicines:

- Nootropic, stimulating cellular metabolism in nervous tissue, protecting neurons from damage.

- Regulating cerebral blood flow, improving the rheological properties of blood.

- Antidepressants, sedatives.

The therapy program involves taking medications that strengthen the vascular wall, regulate cholesterol levels and lipid metabolism, and prevent the formation of blood clots. The patient should avoid head injuries and excessive physical and mental stress. Therapeutic measures include neurocorrection - procedures during which brain functions are redistributed and compensatory mechanisms are activated.

Irritation (irritation) of brain structures leads to behavioral disorders and neurological symptoms, which deteriorates the patient’s quality of life. The pathological condition is a consequence of a primary disease, which is identified by a doctor during a diagnostic examination and is treated first.

753

Complications

Due to dysfunctions of the brain stem structures, respiratory and cardiovascular complications may appear in people against the background of convulsive syndrome - even death in severe cases of irritation. After all, excessive irritation of the subcortical centers leads to hyperpnea, tachycardia, and failure in temperature regulation.

Unlike dysfunction of brain stem structures, irritation of the cortical gyri is a threat of minor and major convulsive attacks. A person is unable to control himself - a deterioration in the condition occurs with the slightest stress, staying in a stuffy room or in conditions with loud sounds or flashes of light. This significantly reduces his social living conditions, chances of obtaining a high position or creating family relationships.

Irritation also has an impact on cognitive functions - this is important in childhood and adolescence, when personality is being formed and skills for vocational guidance are acquired. Without a strong memory and high speed of electrical impulses between nerve cells, the full intellectual development of children is impossible.

The task of parents is to be attentive to their child and consult doctors in a timely manner. If an adult has circumstances such that the brain has been negatively impacted, then their task is to carry out all the appointments of the neurologist so that the rehabilitation is as successful as possible.